Technology Optimsed Lean Performance Management System

Using technology to optimise the lean performance management system in service operations

Ask a lean professional for their top three reasons why projects fail to reach their full potential and an absence of consistent, complete and trusted data is very likely to feature.

Common problem areas include identifying improvement opportunities, actively managing the flow of benefits and demonstrating delivery of those benefits. This limits the effectiveness of improvement interventions but also makes adoption of a consistent lean performance management approach impossible.

There is no shortage of technology available with features intended to help with these challenges. Lean practitioners must be cautious however, to ensure that technology choices do not clash with the desired culture and behaviours. Advancements in data collection technology, in particular, mean that previously inaccessible data can be captured, but careful thought is needed to ensure that people are not distracted from delivering true performance by a perceived need to manage internal metrics.

Many lean practitioners may have mixed feelings about the capability of technology to help them achieve their goals. The number applications (many of which may be highly inflexible) used across even a single value chain can make technology change be slow or impossible.

When it comes to technology to support lean performance management, this can lead to informal, often spreadsheet-based toolsets being used for capturing data, reporting performance, forecasting and planning. Such an approach provides great flexibility and rapid deployment, but anyone who has tried to deploy these solutions at scale will be well aware of the difficulties of ensuring consistency and sustaining good practice. Use of a more robust technology set for this discipline, therefore has many advantages.

But with so much choice available, what is the right technology to use? How do we make sure that a technology will support the people and the process? That it will simplify and not obscure the management challenge.

Here are a few thoughts:

- Seek technology which helps create a responsive “system” by empowering the front line – in particular technology should help the front line manager, not be something they feel they are a slave to.

- Standardise technology across the enterprise to create common language and, through that, encourage a common management process.

- Use technology which can easily align with the existing technology landscape rather than create additional complexity.

- Provide the means of capturing data that reports for people, not just on people and so stimulates engagement and continuous improvement.

Let’s unpack what these could mean in reality.

Creating a responsive system

At the heart of Lean is the ability to respond to customer demand – matching work and resource so that the customer requirements are met without overload (Muri) and without inconsistent working (Mura). A responsive system will move control as close to the customer as possible – empowering team leaders and even team members to make decisions and prioritise in the face of variable customer demand.

Technology can help with this. In the infinitely complex world of service operations with large numbers of activities all happening in parallel with huge variability, it makes sense to bring some computational power to bear in managing the demands being placed on different parts of the organisation. The principle is the same as the original lean manufacturing approaches: help the front line to focus on producing a steady output in line with customer demand.

Make the technology simple enough to be used by the front line, train them to use the technology and trust them to get it right. These are the core elements of a responsive system.

Standardise to create a common language and management process

We should not be too idealistic about front line empowerment. Taiichi Ohno may have said “People don’t go to Toyota to ‘work’, they go to Toyota to think”, but the basis of the scheduling system, of Kanban and Heijunka, were not optional. All the best empowerment starts with a framework – giving people the parameters within which to work.

We believe that technology can be a powerful way of encouraging the behaviours we wish to see as standards. In particular, technology which helps standardise how we manage, not just the way we measure is particularly effective. The capabilities of modern technology can lead to an obsession with measurements which offer limited insight into true performance and move the focus away from using data to plan ahead and create a controlled environment.

Technology which helps standardise the management process gives people a common language, but better yet it makes it easier to work collectively. Rather than trying to control people’s behaviour by rules and diktat, give them tools and apps that make their jobs easier.

Use technology which can easily align with the existing technology landscape

Service operations often have untidy IT application landscapes, with multiple technologies coexisting both to process and transport work. It is essential therefore that technology to support lean performance management can go with the flow, sourcing the data it needs from existing applications without requiring complex IT change.

Technology which is agnostic to the business process and processing technology ensures that the management process can be consistent and optimal across operations and that deployment is both rapid and agile.

Capture data for people, not just on people

We feel that improvements in data capture technology and attempts to re-purpose technology optimised for other environments has led to a return to centralised command structures in service operations. This has led to some very non-Lean approaches, with data being used primarily as a stick to challenge poor performers and very rarely as a means to engage staff and foster ownership of performance.

In a Lean organisation the data should exist to help people not just to stand in judgement over them. Good technology will assist the provision of data that helps people to focus on their jobs, the process and how to drive continuous improvement.

Five ways LEAN THINKING can enhance your business

Successful companies are always looking for new strategies to improve their business and generate more growth. However, introducing a new strategy to an established business structure does not always improve the quality of the business. It is much more valuable to apply a strategy which can tackle the issues within a company, therefore generating a longer-lasting and more productive resolution.

LEAN THIKING is a tried and tested approach which enhances the competitiveness of your offerings by removing unnecessary processes that do not add any value to your customers. It aims to maximise value for the customer, whilst also minimising waste for the company, therefore creating a streamlined and effective structure for business.

Thousands of well-established companies, such as Toyota, Ford and Nike have already seen the advantages of using LEAN within their business and is now being applied in companies of all sizes and in all sectors. Here are five ways that LEAN could help to optimise your business.

1. It reduces costs whilst increasing value

Lean Enterprise Research Centre research has shown that 60% of companies’ have processes in place which do not add significant value to the business. This means that a huge amount are wasting their money and resources on flawed activities without even realising it.

LEAN THINKING works by pinpointing exactly what processes add value to the business and which can be removed without causing damage. Cutting out these ‘waste’ activities from the business allows companies to reduce their costs and also increase value by focusing their resources on areas that are more productive and worthwhile.

2. It gives you an advantage over your competitors

No matter which industry your business is in, it’s important to stay ahead of your competitors. Consumers are always looking for the best quality and the lowest prices, which is sometimes very difficult for businesses to keep up with.

LEAN thinking provides businesses with the means to produce top quality products/services for their consumers, without having to drastically increase their prices. Incorporating LEAN not only helps businesses to cut down on unnecessary costs, but it also strengthens the productivity of the company so that the quality of the product/service is maximised. This allows LEAN businesses to have a distinct edge over their non-lean competitors.

3. It improves your company’s reputation

A good company reputation not only attracts new customers, but it also ensures that existing customers remain loyal. Consumers like to know that they can trust the organisation they are buying from, and even do extensive research to find out whether both the product/service they are purchasing or the company they are buying from are reliable.

When a company has LEAN in place, it adds a certain level of reassurance for the consumer. LEAN aims to provide the right quality for its customers, who are therefore more likely to trust the company and perceive their purchases as good value. Once a company becomes known for providing good quality products/services, their excellent reputation will help the business to build and grow even further.

4. It raises employee morale

An efficient, well-run company with smooth, flowing processes is a much more enjoyable environment for employees to work in. Not only do they get more job satisfaction from being a part of its success, but a good company will also put more emphasis on empowerment and personal development for the workers too.

The LEAN concept believes in encouraging employees to get as much as they can from their career by training managers to be more like coaches or leaders rather than a ‘boss’. This not only helps employees to learn and progress more in their job, but it also creates a much better working environment for them. Looking after your employees, raising their morale and engagement will not only boost productivity levels significantly, and if you are known for being a good company to work for, you will attract staff with high skill sets.

5. It is more environmentally friendly

Many people are sceptical about making their company more environmentally friendly. It is often associated with being inconvenient, time-consuming and costly, which is both unattractive and impractical to many businesses.

LEAN, however, embraces an environmental approach but in a way that also benefits the business. The LEAN concept is to achieve more, but with as little resources as possible. This is done by cutting out all of the waste which has little or no value to the business so that the quality of production stays the same, often with the knock on effect of becoming more environmentally friendly. As well as being more efficient and cost-effective, promoting yourself as an environmentally friendly business is also a great way of giving yourselves that edge over your competitors.

Value Confusion: The Problem of Lean in Public Services

Introduction

For well over a decade continuous improvement approaches have been formally applied in the public sector in the UK and elsewhere, in an attempt to improve service quality and streamline processes, often in response to cuts in public expenditure budgets imposed by governments.

Many public services in the UK – including defence, healthcare, police, higher education, central and local government – have now, to a greater or lesser extent, implemented continuous improvement (CI) programmes of various shapes and sizes. However, while there are numerous examples of successful initiatives at a process level, questions remain about whether real systemic changes are being made that will produce the long term sustainable CI culture desired.

This article examines the nature of the lean thinking that has been embraced and calls for a debate on the development of a new definition of lean for public services. It contends that the adoption of an unadapted lean approach that is primarily geared for the private competitive market has meant that public service organisations have misunderstood the nature of value in the public sector, which has created counter-productive distractions and raises issues on lean’s ability to help engineer long term, systemic change.

Lean & Competitive Advantage

This discussion about lean’s role in improving public services starts with examining the purpose of lean thinking and lean methods. The roots of contemporary lean thinking can be traced to the development of the Toyota Production System (TPS) after the second world war and for Taiichi Ohno – Toyota’s chief engineer and architect of the system – it can reasonably be deduced that the ultimate aim of TPS was to create competitive advantage for Toyota, so that buyers of cars chose a Toyota model over those of its competitors.

This was achieved by producing a vehicle that delivered clear value for customers in terms of its cost, quality, reliability, design, performance and so on. The production system’s design was influenced by a post-war environment characterised by shortages and constraints and TPS’s particular ability was to be effective in removing waste from processes and creating flow, thus enhancing customer value adding activities and so creating additional capacity that could be used to sell more cars and expand the business.

The lean approach, as it was later termed by Womack, Jones and Roos, based on TPS principles fitted perfectly into the free market competitive model and from the 1980’s many companies, starting with those in the automotive and aerospace sectors readily attempted to embrace the ideas. Thus contemporary lean thinking became a common feature in many businesses strategies and was able to provide an actionable implementation framework that could be adapted for different business environments and sectors.

The lean approach, as it was later termed by Womack, Jones and Roos, based on TPS principles fitted perfectly into the free market competitive model and from the 1980’s many companies, starting with those in the automotive and aerospace sectors readily attempted to embrace the ideas. Thus contemporary lean thinking became a common feature in many businesses strategies and was able to provide an actionable implementation framework that could be adapted for different business environments and sectors.

The essence of the free market model is that the customer is able to choose among competing offerings and will part with his or her money to the producer that can deliver the greatest perceived value. This classic model positions the private consumer – the customer – as the arbiter of value, whose decisions will ensure that competing businesses will strive to be more effective in meeting his or her needs and delivering the right products at the right prices.

Marketisation of Public Services

UK public policy in the 1980’s was dominated by the neo-liberal thinking of Prime Minister Thatcher and her Conservative governments, which placed a strong emphasis on the virtues of competition and a view that the size and influence of the state should be reduced. Public services were considered bloated, with inherent inefficiencies and a drag on economic growth.

New Public Management (NPM) emerged as the supporting doctrine to this policy, that advocated the imposition in the public sector of management techniques and practices drawn mainly from the private sector, as according to NPM greater market orientation would lead to better cost-efficiency, with public servants becoming responsive to customers, rather than clients and constituents, with the mechanisms for achieving policy objectives being market driven.

NPM reforms shifted the emphasis from traditional public administration to public management and this included decentralisation and devolution of budgets and control, the increasing use of markets and competition in the provision of public services (e.g., contracting out and other market-type mechanisms), and increasing emphasis on performance, outputs and a customer orientation.

Some parts of the public sector left it completely through privatisations, such as utilities, transportation and telecommunications; semi-autonomous agencies were created, such as the DVLA and outsourcing major capital projects through private finance initiatives became common.

The customer became further entrenched in the public sector psyche when John Major’s government introduced the Citizen’s Charter in 1991, which was an award granted to institutions for exceptional public service. As its website stated, “Charter Mark is unique among quality improvement tools in that it puts the customer first”. Its self-assessment toolkit contained six criteria, the second being actively engaging with your customers, partners and staff.

The customer became further entrenched in the public sector psyche when John Major’s government introduced the Citizen’s Charter in 1991, which was an award granted to institutions for exceptional public service. As its website stated, “Charter Mark is unique among quality improvement tools in that it puts the customer first”. Its self-assessment toolkit contained six criteria, the second being actively engaging with your customers, partners and staff.

The Citizen’s Charter was replaced in 2005 by the Customer Service Excellence standard, led by the Cabinet Office, which aimed to “bring professional, high-level customer service concepts into common currency with every customer service by offering a unique improvement tool to help those delivering services put their customers at the core of what they do”. This offered public sector organisations the opportunity to be recognised for achieving Customer Service Excellence, assessed against five criteria, which included ‘customer insight’. To date, several hundred public sector organisations are listed on its website as having achieved Customer Service Excellence.

When the formalised and packaged versions of contemporary lean thinking and CI appeared from the 1990’s, it was a logical step for public sector organisations to adopt these approaches as part of the NPM agenda, especially as continuous improvement was integral to initiatives such as Citizen’s Charter and Customer Service Excellence, as these could help them cope with increasing demand for their services, coupled with reducing budgets and the drive to be customer focussed. Techniques to reduce waste and costs were particularly attractive, even if the resultant released capacity could rarely be used to ‘grow the business’ as it could be in the private sector.

Thus public services readily and enthusiastically embraced all aspects of lean philosophy, integral to which was a market orientation, where the identification and delivery of customer value was paramount.

The Nature of Value & the Customer in Public Services

A process is a process, whether it is in the private or public sector and so it can be argued that process thinking, as defined by System Thinking advocates such as W Edwards Deming, is equally applicable to both, since waste removal, improving quality, reducing lead time and enhancing flow are universal aims.

So while it seems reasonable for public services to use the techniques at a process level to produce some public good, it is argued that by including an explicit customer orientation, it leads to a range of problems.

A key issue is the NPM contention that there are customers in public services for whom value is identified and then delivered. The classic characteristics of customers is their ability to choose between different products and suppliers and spend their money according to the offering that delivers the greatest perceived value. However, in this sense, a customer rarely exists in a public sector context.

Instead, according to writers such as Teeuwen, they are citizens, who can have several roles at different times, including that of user, subject, voter and partner; occasionally, the citizen can be a customer, such as when choosing among transportation options, but it is not the dominant role. To this list could be added patient and prisoner and even obligatee, as Mark Moore describes taxpayers, who clearly have no individual say in taxation, but simply an obligation to pay up. In most of the roles, the individual citizen does not ‘specify the value that is to be delivered’ and has no choice in service provider.

Therefore, it is suggested that the concept of an individual customer deciding on what constitutes value is flawed in a public sector context. This can distort service design, lead to the use of inappropriate or unhelpful measurements with the numerical quantification of quality through targets, create expectations in citizens that cannot be met (leading to frustration and dissatisfaction) and lead to confusion regarding the true purpose of the function or service.

Public Value, not Customer Value

Mark Moore in his seminal work Creating Public Value (1995) recognised the problem that the public sector manager has in working out the value question. Whereas his or her private sector counterpart has a clear idea that the individual consumer is the ‘arbiter of value’ and makes choices on buying competing products based on the perceived value delivered, in the public sector he contends that the arbiter of value is not the individual, but the collective – that is, broadly society in general, acting he says “through the instrumentality of representative government” – and likely to be made up of service users, tax payers, service providers, elected officials, treasury and media.

Mark Moore in his seminal work Creating Public Value (1995) recognised the problem that the public sector manager has in working out the value question. Whereas his or her private sector counterpart has a clear idea that the individual consumer is the ‘arbiter of value’ and makes choices on buying competing products based on the perceived value delivered, in the public sector he contends that the arbiter of value is not the individual, but the collective – that is, broadly society in general, acting he says “through the instrumentality of representative government” – and likely to be made up of service users, tax payers, service providers, elected officials, treasury and media.

Identifying what value to produce for a public service therefore has little to do with an examination of an individual’s needs and preferences. There is also no requirement to win custom and market share through a variety of product delighters, innovations and exceptional customer service.

The notion of public value has echoes of the 19th century Utilitarianism philosophy of Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, which stated that the goal of human conduct, laws, and institutions should be to produce the greatest happiness of the greatest number. Other significant contributors to the public service value debate in the UK include John Benington at Warwick University (who has collaborated with Moore) and John Seddon, whose CHECK improvement methodology focuses on the need to identify purpose as a prime initial task in service improvement, rather than go down the customer/value route. Identifying purpose appears to have strong resonance with public value.

Identifying public value is not an easy proposition and because decisions are almost always about how to allocate scarce resources, there will be compromise and invariably an individual’s demands will be subordinate to those of society in general.

Moore contends that the pursuit of public value aims requires the support of key external stakeholders, such as government, partners, users, interest groups and donors. Public sector decision makers must be accountable to these groups and to engage them in an ongoing dialogue and build a coalition of support to create this platform of legitimacy.

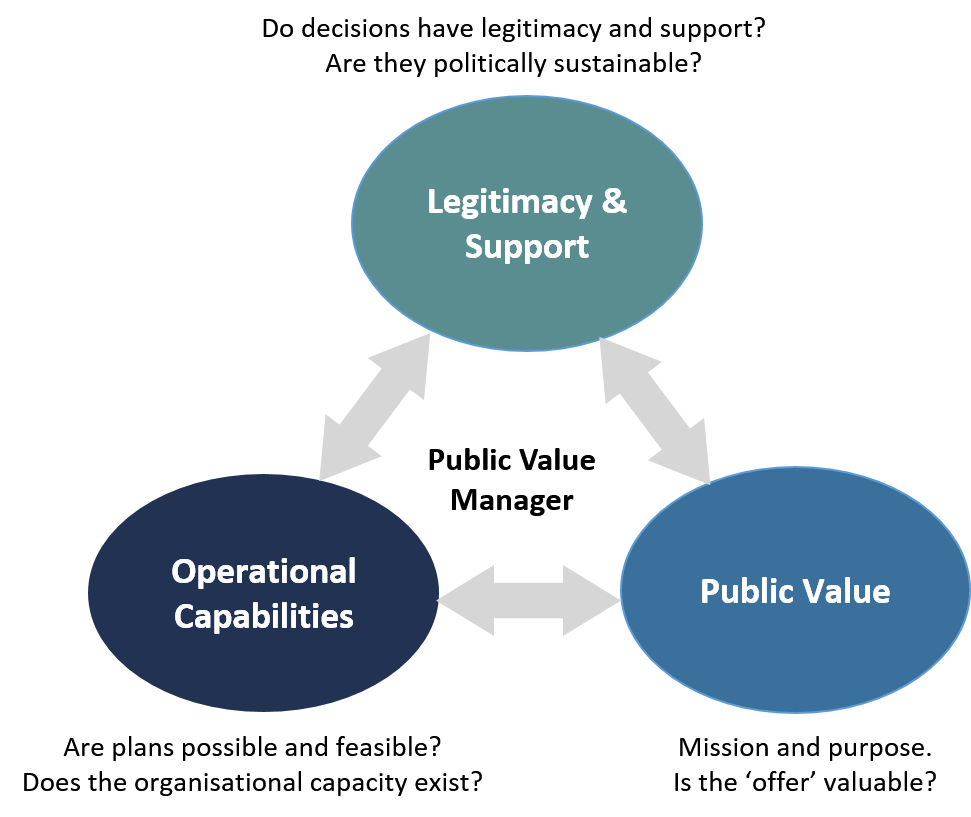

He describes a “strategic triangle”, which represents the dimensions that the public service manager needs to consider in developing a course of action, comprising of the authorising or political environment (legitimacy and support), the operational capacity and the public value (purpose). The proposition in the strategic triangle is that purpose, capacity and legitimacy must be aligned in order to provide the public manager with the necessary authority to create public value through a particular course of action.

Service v. Value

As a result of the NPM agenda, citizens have been led to believe that they are customers of public services, just like they are customers of private businesses and therefore have the same service expectations of public services as when they transact with, for example, retailers John Lewis or Amazon. Similarly, public sector employees have been encouraged to treat the recipients of their services like private sector customers.

This does not mean that public services should not strive to deliver a productive and positive experience to its users, patients, obligatees etc., especially as the outcome of effective process thinking should supply exactly that. As taxpayers, citizens have a reasonable expectation to receive quick, effective and courteous service, but this may have little to do with delivering public value or in achieving its prime purpose.

Indeed, public value is often at odds with private value; consider airport runway expansion in the south east of England, the route of the HS2 train from London to Birmingham, the creation of dedicated cancer drug funds, the gritting of roads in icy conditions and the building of flood defences.

Many public service measures, such as in healthcare, have an explicit customer service orientation and a significant amount of debate and political energy is spent scrutinising these. This is not to say that waiting times for treatment or answering a phone call are not relevant, but that they distract from the important question of assessing and understanding the public value that the particular service should strive to deliver.

HM Revenue & Customs (HMRC) regularly receives significant media and public criticism and a report by the National Audit Office in 2012 into its customer service performance concluded that “while the department has made some welcome improvements to its arrangements for answering calls from the public, its current performance represents poor value for money for customers.”

In 2014-15, HMRC collected a record £518 billion in total tax revenues, employing some 65,000 people. In 2005-06, it collected £404 billion with around 104,000 staff; this means that over a decade it has collected 25% more revenue with 38% fewer staff. It has also made cost savings of £991 million over the past four years. HMRC delivers public value by maximising the tax take using as few as resources as practical, though clearly it does have service obligations to its users.

Interestingly, the National Audit Office report comments that “HMRC faces difficult decisions about whether it should aspire to meet the service performance standards of a commercial organization. It could do only by spending significantly more money or becoming substantially more cost effective.” This is the nub of the dilemma faced by many public services and a key question is whether it should indeed strive to be like a commercial organisation and expend more and more resources in doing so. However, service should not be confused with value.

In the private sector there usually a clear relationship between the price paid and the service received. The Kano model refers to performance or linear attributes of an offering – ‘more is better’ – where increased functionality or quality of execution will result in increased customer satisfaction. For example, we can choose the speed of delivery of an online purchase by selecting either the free (3 to 5 days), standard (2 days) or premium (next day) service and we will make a conscious decision to pay for the one we desire.

This scenario takes place in some UK public services, such as obtaining a new passport, where there are differently priced one week Fast Track service and one day Premium service, though in most public services a direct service-price relationship does not exist.

Conclusions & Future Discussion

The classic lean thinking approach that emerged from TPS is ideally suited to organisations operating in a competitive market environment because of its focus on customer value, its ability to help create competitive advantage, grow market share and ultimately enhance shareholder value. This article contends that the wholesale adoption of this approach by public services is inappropriate, as it does not recognise the difference between private value and public value.

Just as there was a debate in the early 2000’s about whether the lean thinking that was developed and used in manufacturing was suitable for service environments, there needs to be a debate about how it should be adapted for public services and in particular the move towards adopting a public value perspective.

The following suggestions can help inform this debate:

- Lean practitioners in public services should move away from an overt focus on individual customers and the value they demand. Those using Womack and Jones’ first lean principle (‘specify value from the standpoint of the customer’) should adapt it so that the emphasis is on specifying public value that is to be delivered, linked to the purpose of the organisation.

- There needs to be a redefinition of what it means to be a customer of public services; while it is probably too late and counter-productive to abandon the term customer, a new specific public service lean vocabulary will help provide clarification. As Mark Moore comments “the individual who matters is not a person who thinks of themselves as a customer, but as a citizen”.

- Lean leadership in the public sector should primarily focus on understanding and identifying public value. Mangers need to focus specifying the public value that they are trying to deliver and make it clear that this can be different or even in opposition to private value. The key question that a lean manager needs to ask, according to Benington and Moore, is not what does the public most value? but what adds most value to the public sphere?

- The recipients of public services – citizens – need to be educated as to what they can reasonably expect from the public sector in terms of service levels and understand that when they ‘consume’ public services, they are not customers in the same way as when they consume in the private market; they do not have the same rights, advantages or privileges. The level of service provided in delivering services needs to be balanced against the cost of providing it. Citizens also need to understand that public value will sometimes be at odds with private value.

- Public services generally do not present products to a market in the same way that private companies do, the latter then plotting the optimum value stream for delivery to the customer. Rather, they usually wait for demand for services and react; this suggests there should be less emphasis on value stream management and more on demand analysis and management – with a greater emphasis on understanding the nature of the demand (quantity and quality), proactively attempting to limit and control it in many circumstances.

Few would argue that effectively applied process thinking cannot have a positive role to play in improving public services and it is contended that adopting a public value perspective will enhance its overall impact.

But the shift from private value to public value is not without its challenges; several decades of NPM thinking has created a mindset that may be difficult to change and moving to more utilitarian position in an age of individualism may be a daunting prospect. Mark Moore says that a key reason why public value is a challenging idea is because it brings us out of the world of the individual and back into the world of interdependence and the collective; and that, he claims, “runs contrary to the direction that everyone seems to be going in”.

References & Further Reading

Download a pdf version of this article

Watch a Mark Moore video in the LCS website Video area.

Building our Future: Transforming the way HMRC serves the UK (2015), HMRC

Creating Public Value (1995), Mark Moore

Customer Service Excellence website: www.customerserviceexcellence.uk.com

Freedom from Command & Control (2005), John Seddon

Lean for the Public Sector (2011), Teeuwen

Lean Thinking (1995), Womack & Jones

National Archives, Charter Mark website: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20040104233104/cabinetoffice.gov.uk/chartermark/

National Audit office website: www.nao.org.uk

Public Sector Management (2012) Norman Flynn

Public Value: Theory and Practice Paperback (2010), Benington & Moore

Service Systems Toolbox (2012), John Bicheno

Systems Thinking in the Public Sector (2010), John Seddon

The Guardian: www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2016/mar/02/narcissism-epidemic-self-obsession-attention-seeking-oversharing

The Machine that Changed the World (1990), Womack, Jones & Roos

The Equation of Lean

“I’m sorry, but all our agents are busy at the moment…”

We’ve all experienced this apologetic message on a Monday morning when we call a service centre to make that claim, book an appointment, or request service. They are experiencing “high levels of demand” and you’re invited to go to a website, or call back when its less busy or simply hold on …and naturally, they really do “value your custom”.

Of course, if they really valued my custom they would find out that what I value is a short queue, so I do not wait long for someone to answer my call, who has the capability to address my query or solve my problem quickly. You also get the impression that they are genuinely shocked by the call volumes on that particular morning and they are pulling out all the stops to keep the show on the road and reduce the queue. However, the question persists ‘do they really understand the nature of queues and are they doing anything about them?’

Queues

Understanding the nature of queues should be a key concern of any service operations manager, since demand will never be even and service processing times will never be the same. Queues are therefore highly prevalent in all forms of service and have the potential to create waste and negatively impacting flow, quality, customer satisfaction, cost and ultimately competitiveness and profitability.

John Bicheno has long focused on queues and their impact and provides a full discussion in The Service System Toolbox, as well as promoting several dice games that illustrate the principles clearly and simply. John focusses on Kingman’s Equation as a means to understand queuing phenomena and has labelled it the equation of lean due to its significance and the insights it can bring for managing lean service operations.

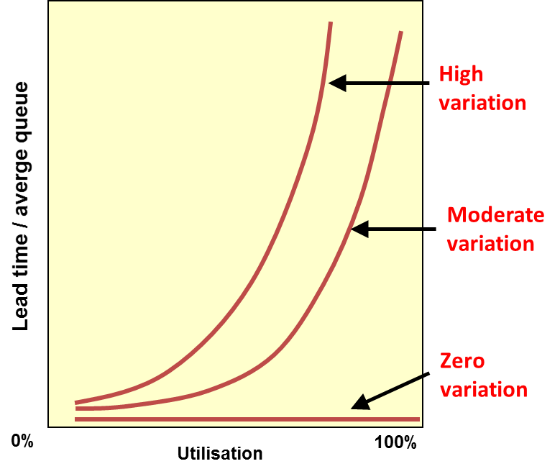

While you do not necessarily need to immerse yourself into the statistics behind the equation, familiarity with its fundamental components is critical. Put simply, Kingman’s equation states that three variables influence the length of the queue, which are:

- Arrival variation

- Process variation

- Utilisation

The graph shows the queuing theory relationships, where the vertical axis is average queue length, the horizontal axis shows capacity utilisation (that is, average arrival rate divided by average service rate).

Key points to note about the graph are:

Key points to note about the graph are:

- Queues approach zero when there is plenty of capacity.

- Queues get worse when arrival rate of customers nears the capacity, which means the curve is exponential not linear: so the busier its gets, the worse the queue.

- When demand is about 80% of capacity, the queuing problems start, so as a rule of thumb, you need 25% more capacity than demand to provide a reasonable service.

- Working at higher utilisation will clearly risk upsetting customers.

- If there is no variation, the average queue time will be zero.

- The range or uncertainty in queue length is highly dependent on utilisation; when it is low the range is small, when it is high wait time in the queue is highly unpredictable.

Note that the aforementioned dice game will produce an output similar to the graph above, clearly illustrating the queuing, as well as the immutable power of the laws of statistics.

So on that Monday morning in the call centre, as demand exceeded 80% of capacity, waiting times started increasing rapidly and service levels nosedived and the apologetic voice message kicked in. Any manager or his accountant colleague who thinks the operation could operate at 100% capacity does not appreciate the statistical reality.

Variation & Flow

A key lesson from Kingman’s Equation is that variation is the enemy of flow and if we can reduce both arrival variation and process variation, we will be able to process more, even if we have less capacity.

There is a wide array of methods to control arrival variation, including off-peak pricing, extending opening hours and special offers, scheduling appointments, moving low priority work to quiet times, though many businesses actually make matters worse by offering quantity discounts or having sales targets that result in an end of month activity peak. However, most of the time in many sectors there is a predictable pattern to demand volumes and it is only due to ‘special cause’ events that things change.

Process variation can be narrowed by tactics including improved staff flexibility, specific training, better qualified operators, smaller batch sizes, adopting a right-first-time mind-set, reducing product variants, better customer communication, six sigma tools and standard work. The latter is popular due to its status in the traditional lean toolbox, though too much standardisation risks causing high levels of failure demand and an inability to meet customer needs, since it can prevent the system from being able to absorb the natural customer demand variety that is an innate feature of services. This tends to be different in manufacturing, where the aim is try and remove process variation completely, as well as adopting load levelling approaches like Heijunka.

Implications for Lean Managers

An understanding queues, what causes queue length and a recognition of statistical variation is a critical competency of a service manager. Indeed, one of the five key leadership competencies that the LCS suggests as part of its framework is the ability to problem solve, understand variability and waste.

Kingman’s Equation draws attention to the relationship between three of Toyota’s chief concerns, namely Muda (waste), Mura (unevenness) and Muri (overburden), which are interlinked and together enable a better understanding of lean, and of course the latter two are a particular issue in services.

A further implication is that a prime focus for a lean service improvement team should be on demand analysis and understanding, both in term of demand volumes and the nature of what customers require. In particular, this will enable a focus on failure demand (that is, demand from customers caused by a failure to do something right the first time and the opposite of the value demand you want). Reducing failure demand can have a significant impact on queue length.

The challenge for the service manager is to decide on the right cost:service level trade-off that reflects customer expectations and the overall service proposition being put to the customer. Allocating resources to provide extra capacity may improve the quality of service, but that comes at a high price, which the customer may not be prepared to pay. It may lead to development of different products offering varying levels of service to different market segments, or focusing on what Kano refers to as performance and linear product attributes (“more is better”) for which customers are prepared to pay more.

In making such decisions, what is clear is that the service manager should have some idea where they are on the Kingman Equation curve so they can plan effectively and get a better appreciation of the system in which they are operating.

As for that recorded message received while in the Monday morning queue, perhaps it should more accurately state “good morning; today we have made a business decision to commit a level of resources to answering the phones that, given the high call demand that we knew was coming, will result is you waiting a long time in a queue. Hard luck, but it keeps costs down!”

Reference & Further Reading

The Service Systems Toolbox, John Bicheno (2011)

The Lean Games and Simulations Book, John Bicheno (2014)

Download a pdf version of this article.

Applying Lean in Sales & Marketing: Process Thinking

This article was written by Simon Elias of the LCS and Richard Harrison of Sales Transformation Partnership.

Introduction

While lean thinking is increasingly being applied beyond the operations arena in many organisations, sales and marketing (S&M) appears to have been particularly immune to the lean mantra. The reasons behind this are not particularly well documented or researched and probably include the reluctance of S&M managers to view what they do as definable ‘processes’, a belief that they operate in a black box world of relationships and the art of selling and that all the ‘lean stuff’ is just for the shop floor.

At this stage it is worth noting that the term ‘sales and marketing’ covers a broad array of activities, including sales management, business development, advertising, market research and planning, product development, direct marketing, communication, PR, etc. Furthermore, there are different sectors – for example, FMCG, consumer durables, business-to-business (B2B) – each of which have their own approaches and methods. This article’s focus is the classic sales management and business development function in B2B relationships and while lean principles and techniques can no doubt be applied to all areas, a degree of adaptation will invariably be required.

Engaging with the S&M Audience

Lean’s focus on identifying and delivering value to customers should make it a prime concern of S&M people, who are generally charged with that task in many organisations. Most lean advocates would probably claim that the concepts and principles of lean are just as relevant to the S&M function as any other part of the organisation, since the need for short lead times, high quality, even flow of activities, minimising waste, continually improving are just as applicable to selling the business’s products or services.

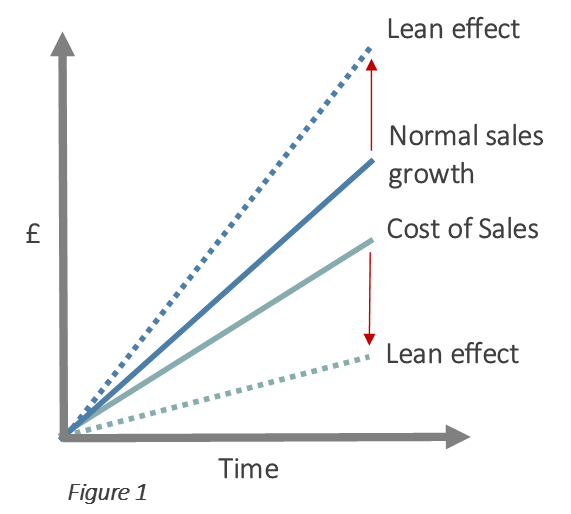

But why should S&M people embrace lean? Well, at a fundamental level, lean promises to not only lower the cost of sales, but also improve sales growth, as illustrated in Figure 1. Of course, this is not guaranteed and there are several other factors that will influence matters, such as general market conditions and competitor behaviour, but the opportunity for this win-win situation should been enough to persuade S&M sceptics to embrace lean ideas.

The key task is to engage with S&M managers in a way that will make them want to positively adopt lean, so that they think in terms of processes and value streams and start to examine how they approach their work and re-design it along lean lines. The behavioural change required may be challenging, though appealing to self-interest certainly has a place, especially since the culture of bonuses and incentives is all pervading in the S&M world and an improvement methodology that has the potential to make targets easier to achieve is bound to raise inquisitive eyebrows.

Finding the right way to communicate is also critical, since the language of lean is a long way off the language of S&M and so some translation is necessary to ensure that this does not become a barrier to acceptance.

Process Thinking in S&M

One of the great system thinkers and influencers of lean thinking, W. Edwards Deming, said “if you cannot define what you are doing as a process, you do not understand what you are doing”, so unsurprisingly process thinking is at the heart of lean. It is not possible to develop a truly lean organisation if you cannot define what you do, how you produce or deliver, what the organisation does and how it does it. All organisations are built on processes, whether purposefully defined or not, and processes support the value stream and business strategy.

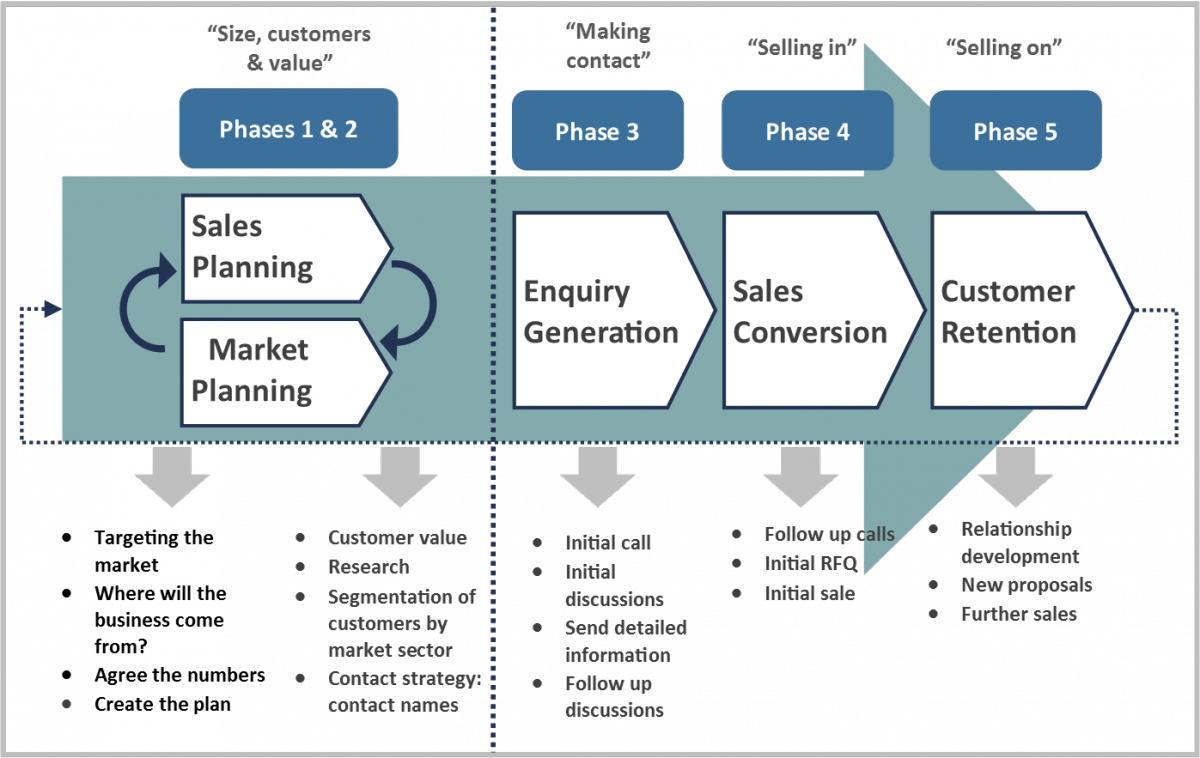

Anecdotal experience suggests processes are often not fully understood in S&M and particularly the case with senior S&M managers. It is therefore important to bring process thinking into the centre stage of S&M planning and the S&M Process Model is an example of a vehicle to achieve this, as shown in Figure 2.

The model emphasises the need to focus on four core S&M processes: sales/market planning, new enquiry generation, sales conversion, and customer retention (which includes added value services). S&M management must ask the following questions about their capability to deliver:

- How capable is the process to generate sufficient new enquiries of the right type (so you can actually produce and deliver the product/service offering profitably)?

- How capable is the process at converting new enquires from either new or existing accounts into actual sales (the conversion rate)?

- How capable is the process at maximising sales by offering additional product/service offerings to existing customers once a relationship is formed and trust established?

- How capable is the process at retaining customers of the right type?

These processes drive S&M performance and if one or more is not operating effectively, then the root causes need to be identified and addressed in order for it to improve.

Lean thinking principles and techniques can be used to develop a performance improvement plan and maintaining customer focus – which will include, for example, identifying the root cause of problems, removing waste and bottlenecks, improving process flow and gaining a better understanding customer needs.

Experience suggests that in SMEs the overall process is weak at the front end, with typical symptoms being an over reliance on one or more existing customers, a lack of selling skills and ability to develop relationships. In larger organisations, there are often issues towards the middle and end of the model, such as the inability to sell additional products to existing customers or issues with losing customers through poor relationship management.

Lean Thinking Principles

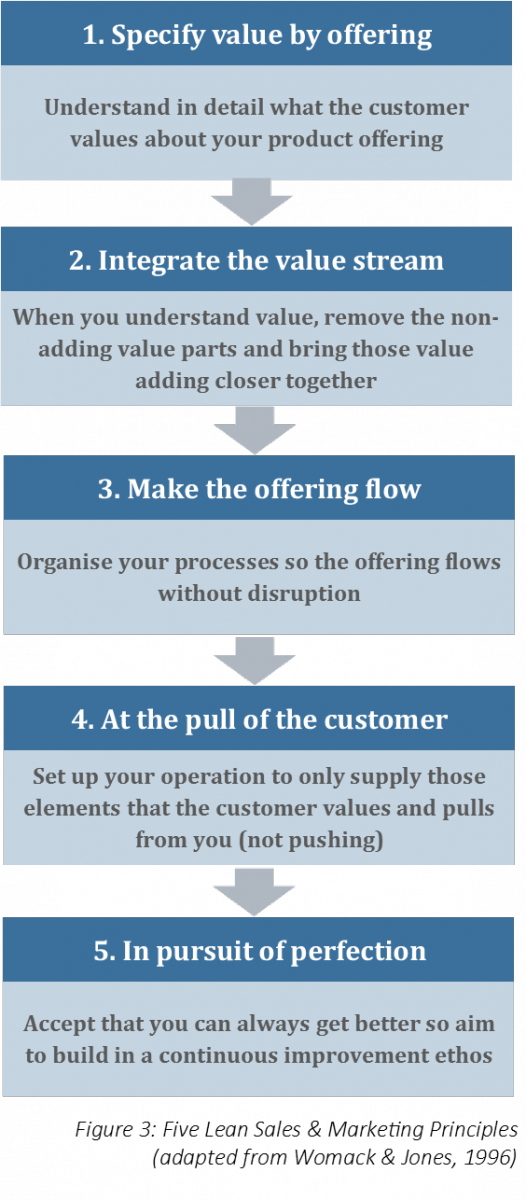

Womack & Jones in their seminal book Lean Thinking proposed five ‘lean principles’ that can be used as a framework to guide lean implementation. These principles can be readily adapted and used in an S&M context and provide an overarching framework for developing a lean S&M approach, as illustrated in Figure 3.

The first principle – understanding what the customer actually wants – (the voice of the customer – VoC) is central to lean thinking and, not surprisingly, equally fundamental to S&M. As those closest to customers, the S&M function, is usually tasked with understanding their needs and defining the detailed offering, though how much of the understanding is based on objectivity and how much on subjectivity is a moot point. A further complication is that in some sectors actually identifying the customer is problematic, as buyers are not always the final consumers of the product.

The first principle – understanding what the customer actually wants – (the voice of the customer – VoC) is central to lean thinking and, not surprisingly, equally fundamental to S&M. As those closest to customers, the S&M function, is usually tasked with understanding their needs and defining the detailed offering, though how much of the understanding is based on objectivity and how much on subjectivity is a moot point. A further complication is that in some sectors actually identifying the customer is problematic, as buyers are not always the final consumers of the product.

The second principle is about ensuring that all the elements of the S&M process are integrated and flow along the value stream. The four core processes of the value stream are the key drivers, each with specific phases of activity which should only comprise of value adding activities.

Typical non-value adding (wasteful) examples include:

- Using substantial resources to collect customer information, for example from surveys, and then not being able to interpret it or gleaning no insights from its analysis.

- Having a customer care programme which is misaligned to the specific needs of the market.

- Spending significant resources generating sales leads for the wrong type of customers.

- Giving too much attention to customers of the wrong type.

- Producing reports that are not read, do not lead to action or do not inform decision making.

- Multiple approval sign-off levels.

Waste removal can be achieved by undertaking a mapping exercise that enables non-adding value activities to be highlighted and considered for elimination. Value stream mapping is a valuable skill for individuals and teams. There are many types of mapping tools and having an appreciation of where and when to use the appropriate mapping tool can prove a real benefit to improving S&M performance. For example, the Big Picture Map might be used to scope out and gain a high level overview of a situation – it copes easily with the bigger issues and enables a wider perspective of an overall picture to be achieved. At a smaller scale, a four field map might be used to design or redesign a quotation process with the objective of reducing the time taken to process and enquiry.

The third principle is about flow and many lean thinkers contend that this is the essence of lean – ensuring that value adding activities flow quickly and smoothly through the value stream. From an S&M perspective, it is about making sure that all elements in each part of the four core processes exhibit continuous flow in order to make them efficient and effective.

Common symptoms of a lack of flow in S&M processes include:

- Overburdening of people through excessive work load backlogs in specific parts of the process.

- Excessive variation in process that are meant to be relatively standard.

- Unevenness of the workload demand.

- Too much non-value adding activity (waste) in processes

Principle four is only take action at the ‘pull’ of the customer. The opposite of pull is ‘push’ – that is, trying to give the customer something that may not be valued. Pull in classic lean manufacturing terms is about ensuring that a product is only made for known demand, avoiding a make to forecast mentality (some even contend that forecasts are either ‘lucky or lousy’!).

In the S&M world, the benefits of adopting this approach are specifically related to work patterns throughout the process, in that work is organised only in response to pull, or real demand, from the customer. Specific benefits include:

- Highlighting issues with workflow, including backlogs

- Enabling an alignment of skilled resources to demand

- Highlighting opportunities for continuous improvement

The fifth principle – in pursuit of excellence – is where every activity undertaken by every person in every part of the S&M process is focused on adding value aligned to the needs of the customer.

It is an ongoing mission, where those working on S&M processes are trained to recognise and then remove successive layers of non-value added activities as part of continuous improvement practice. This represents a cultural shift, require behaviour changes and takes time to embed.

Summary

S&M managers seeking to improve performance will find that adopting a lean approach offers them an effective and appropriate set of tools and techniques to help in realising their goals. When considered as part of a wider integrated lean transformation programme, the benefits will be felt across the business.

The benefits are primarily based on introducing process thinking and understanding to S&M staff. Process thinking has not generally been part of the vocabulary of S&M managers, who perhaps consider it as confining and restrictive, stifling the creativity required in their work. However, it can be argued that adopting lean ways and ‘managing by fact’ does assist in creative thinking and defining direction. For example, ‘visioning’, is a key part of effective direction setting and strategy formation and by gaining a much clearer picture of what customers’ value, S&M managers will be able to better align their offerings with the needs of their customers and more effectively than their competitors.

Understanding the concept of the value stream can offer real benefit to the S&M manager, as this clarifies what actually does and does not add value from their customers perspectives. Having the ability to visualise value streams and the processes within them, helps in root cause analysis and helps convert reactive behaviour, where processes are out of control, to highly focused and proactive behaviour where processes are in control. And of course, processes in control will flow more effectively.

Lean’s focus on customer value as a route to competitive advantage should sit very comfortably with the S&M community, since this should be their prime task in any business and getting a good understanding of the VoC has the potential to be a real differentiator and order winner. There are a range of VoC tools to help the S&M practitioner gain deep insights into customer value, as well as develop strategy, refine existing products and define new products.

Lean is applicable to S&M, since S&M is made up of processes, just like other parts of a business; and once activities are viewed and analysed as processes, then the opportunities for improvements are revealed. The particular advantage of this in S&M is that resultant productivity improvements can not only reduce the resources required to generate sales, but also increase sales through a better understand of customer needs.

Behavioural change will probably be necessary in most situations, which is invariably challenging and not without risks and the development of lean culture is a long term journey. However, important immediate gains can accrue as soon as there is a detailed understanding of S&M processes and clearer appreciation of customer value, paving the route for the development of a sustainable, continuous improvement S&M way.

Download a pdf of this article

Gamification & Lean

You may not have come across Gamification, but as it is being heralded as “a powerful tool for motivating better performance, driving business results, and generating a competitive advantage” and several major organisations are using it in areas such as sales/marketing and HRM, for customer engagement, productivity enhancements and behaviour change.

From a lean perspective, Gamification can motivate people by putting them at the centre of the continuous improvement system, aligning them with a greater purpose, giving ‘players’ a sense autonomy and control, and facilitating flow and ‘fun’ through play.

Download the full article: Gamification of a CI System.

Useful links:

“Typically gamification applies to non-game applications and processes, in order to encourage people to adopt them, or to influence how they are used. Gamification works by making technology more engaging, by encouraging users to engage in desired behaviors, by showing a path to mastery and autonomy, by helping to solve problems and not being a distraction, and by taking advantage of humans’ psychological predisposition to engage in gaming. The technique can encourage people to perform chores that they ordinarily consider boring, such as completing surveys, shopping, filling out tax forms, or reading web sites” Source: http://mashable.com