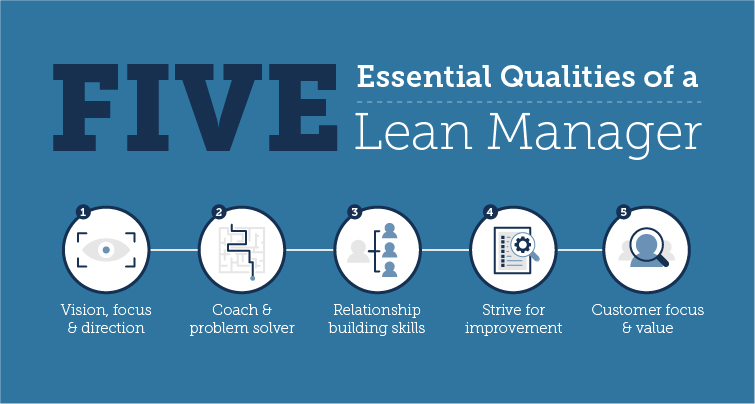

The Five Essential Qualities of a Lean Manager

Lean management (and the leadership implicit within the role) plays an essential role in the operation and success of lean businesses. Without a willingness to adopt a lean leadership approach, companies will struggle to fully benefit from the implementation of lean, as leading influencers will still be fixed in traditional management methods.

Managing lean businesses requires a fresh approach, with managers being considered as coaches, leaders and mentors rather than simply a ‘boss’.

This style of leadership goes hand in hand with the core principles of lean, as it focuses on optimising all aspects of the business, including working relationships between managers and employees.

To help businesses maximise the potential of lean implementation, we have distilled our five essential lean management qualities that every lean manager needs, presented below:

1. Giving vision, focus & direction to the organisation

As forward thinkers, leaders and motivators, lean managers need to be able to provide vision to the business and identify long term goals. Having the ability to set focused targets and continuously reassess goals enables managers to identify which areas of the business are on track and which require refocusing. Lean managers should also be able to view failure to meet their targets as an opportunity to learn and refine underdeveloped processes. This is an essential part of learning which areas of the business has room to improve and grow.

2. Active coach & problem solver

Traditional managers are often criticised for not participating in the workplace enough, which can lead to significant problems getting overlooked and to staff losing motivation. Lean managers are encouraged to spend more time in the working environment, interacting with employees and looking for opportunities to improve processes. That is why lean managers must be able to identify and solve workplace problems confidently, so that they can enhance productivity and continue to make processes flow even better.

3. Good relationship building skills

It is important for lean managers to understand the behaviour of people and build positive relationships with their employees. Being a motivator and a teacher builds rapport with staff and empowers them to take on more responsibility. This results in a happier workforce and increased productivity levels. Conscientious customers will also opt for companies which have good internal relationships. Businesses with a reliable, likeable and enthusiastic manager are more likely to attract loyal customers.

4. Strive for development & improvement

Lean managers should be able to understand how to learn, develop and improve to get the most out of their business and their employees. Constantly searching for new ways to optimise the business will ensure that the company does not stand still or move backwards, but continues to progress. A good lean manager is never fully satisfied with current processes and will always strive to achieve more and continually improve. They are constantly looking to pursue new ideas and find growth areas for development.

5. Customer focus & value systems

Lean thinking prioritises customer value in all business processes, as it helps to establish positive relationships and ongoing customer loyalty. Good lean managers should get to know their customers and use the information to shape significant decisions. Ongoing process improvement and waste reduction will enable all employees provide more value to customers whilst minimising waste and reducing costs. Managers should also encourage employees to adopt the same dedication to high quality and customer value, so that the business remains customer focused throughout.

If you would like more information on lean accreditation or certification, take a look at our

summary web page or get in touch via our contact page.

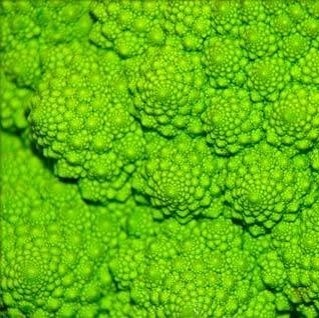

A Fractal View of Lean

“…or why Broccoli is good for you!”

Introduction

Some contend that lean is at a tipping point in its life cycle. Will it wither away as just another business improvement fad, or will it thrive, survive and grow and bring its full potential to bear on business, the public sector and society? This article argues that taking a fractal view of lean will help it take the latter path, enabling it to continue to evolve and help people and organisations improve and prosper.

It first defines fractal and how it relates to lean thinking. It then highlights the potential advantages of this perspective and looks at examples of applying lean at difference scales and variations from individual working behaviours to team ways of working to organisational operating models. It concludes with the practical implications for lean initiatives from taking a fractal perspective.

What is a Fractal View of Lean?

The Fractal Foundation defines fractal as:

“a never ending pattern that repeats itself at different scales. This property is called self-similarity. Although fractals are very complex they are made by repeating a simple process.” (Fractal-Foundation, 2015)

It is contended that lean has its own fractal, since the foundational lean concept of maximising value by minimising waste applies at every scale of work, from how individuals handle daily work and activities, through to team ways of working, value stream optimisations and organisational operating models.

It is contended that lean has its own fractal, since the foundational lean concept of maximising value by minimising waste applies at every scale of work, from how individuals handle daily work and activities, through to team ways of working, value stream optimisations and organisational operating models.

A fractal view of lean taps into a familiar theme. Shea Gunther in Mother Nature Network states that

“the laws that govern the creation of fractals seem to be found throughout the natural world. Pineapples grow according to fractal laws and ice crystals form in fractal shapes, the same ones that show up in river deltas and the veins of your body. It’s often been said that Mother Nature is a hell of a good designer, and fractals can be thought of as the design principles she follows when putting things together”. (Gunther, 2014)

Broccoli is a natural fractal. The Romanesco variety of Broccoli (illustrated) is the ultimate fractal vegetable and exhibits a repeating pattern that displays at every scale. (McNally, 2008).

Advantages of a Fractal Approach

Taking a fractal view of lean has several advantages:

- It helps resolve the confusion between different improvement methodologies. Lean versus Systems Thinking is an example. A fractal perspective suggests that Systems Thinking is simply the application of lean principles at the system or operating model level.

- It broadens the view of lean not only in size and scale but also in breadth. Lean thinking should include any element that can influence the flow of value to the customer: not only process activities but policy, measures and controls, leadership behaviours, skills and structures, daily working culture and technology. Each broccoli has the same design principles but each broccoli has its own unique size and shape. It is the same with lean.

- It generates exciting new areas for development that have received relatively little attention up to now, such as the application of lean thinking at the individual level.

- A fractal perspective supports sustainability by promoting lean culture and behaviours at every scale in the organisation: from the very big to the very small. From strategic operating model designs, to value stream streamlining and intra-team optimisation. And for leadership behaviours at every level from the board to team managers to individual working habits and behaviours. Fractal lean can become part of the organisational DNA.

Breaking Down Boundaries

The spread of lean thinking over the past three decades has often been characterised by boundaries. Industry boundaries, such as manufacturing and service; functional boundaries such as finance, IT and operations; other types of boundary, such as the two levels of Strategic and Operational lean, set out in Learning to Evolve – A Review of Contemporary Lean Thinking (Hines et al, 2004). While boundaries have been helpful in charting the spread of lean, it can be argued they have been unhelpful in creating the perception that lean is constrained within these boundaries.

Comments such as ‘lean is for transactional not creative processes’ or ‘lean is good at incremental change, but we need transformational change!’ or ‘lean works for existing processes but we need completely new processes’ or ‘lean focuses on tools but we need to focus on culture’ are common and suggest the presence of barriers that inhibit lean’s broader application.

A fractal view of lean challenges these self-imposed constraints. It suggests that in every sphere of organisational and individual activity, and at every scale and type of issue there are opportunities to apply lean principles to remove waste and improve performance.

Thinking Big

The following case helps illustrate the application of lean thinking at the operating model scale. Several years ago a global services company was redesigning its sales, service and delivery model. As with many operating model projects, the primary lens was organisational looking at structures, reporting lines, governance, spans of control, roles and responsibilities. There was less consideration of the actual work to be delivered, the volumes and variations of work involved, the types of customer for that work and their requirements.

The new design was completed after several month’s intense activity and a global conference call was organised to announce and explain the new operating model. During the Q&A session the first question was: “how is this new structure going to influence the speed with which we can get new sales proposals approved and out to our customers?” There was a pause and then the answer from the Project Head: “that’s the very next thing that the design team’s going to look at!”

This was one of the core value streams running through the new structure. Its performance deteriorated as a result of the new operating model.

Sometime after, the same organisation repeated the exercise. This time a lean lens was applied, looking at the core value streams, the customer types and their requirements for each value stream and the types, volumes and variations of work that were flowing through each value stream. This lean lens resulted in a radical organisational redesign. Multiple regional centres of excellence were consolidated into two global centres of excellence operating around the clock and with team cells containing the necessary expertise and authority levels to get proposals to customers much faster and with rapid iterative response to specification and budget modifications.

Thinking Small

Much of the focus of lean thinking has been on the system, the value stream and the team. But what about each of us as individuals and our daily working habits and practices? Could lean thinking at a personal level be one of the greatest areas of opportunity? While this is covered to an extent in team based optimisations, using such methods as ‘Day in the Life Of’ (DILO) and ‘Week in the Life Of’ (WILO) these tend to be used at the team abstract level.

Daniel Markovitz explores this area in his book A Factory of One – Applying Lean Principles to Banish Waste and Improve Your Personal Performance. (Markovitz, 2011):

“…while lean has enabled companies to make huge gains in how they get things done, there is a new and vast frontier still waiting to be improved: the daily world of individual work … by applying lean principles to your work, right now, you can reduce the effort and frenzy that characterize your days and get more high quality work done with less stress.”

Markovitz shows with case studies and examples how the principles of value, waste, flow, 5S, visual management, kanban, root cause problem solving and continuous improvement can be applied at the individual level for better results and a more sustainable and balanced way of working.

Although he does not use the lean word, David Allen’s book Getting Things Done, (Allen, 2001), proposes a methodology for individuals to improve and optimise how to get things done. Many have found this methodology helpful in reducing lead and process times and removing waste and re-work from daily activity. Allen argues that most human beings are ill prepared for the high levels of demand and wide variation of work that hits them on a daily basis. Most have no formal process for handling this demand and simply muddle through, often with large amounts of stress and rework involved.

Allen proposes a clear process to handle work:

“The core process I teach for mastering the art of relaxed and controlled knowledge work is a five-stage method for managing workflow. No matter what the setting, there are five discrete stages that we go through as we deal with our work. We (1) collect things that command our attention; (2) process what they mean and what to do about them; and (3) organize the results, which we (4) review as options for what we choose to (5) do.”

He also proposes a series of rules to minimise lead and process times. A good example is the three-minute rule: if you can do something in less than three minutes then do it right away, otherwise write it down and avoid the rework of constantly trying to remember multiple items.

Thinking Fractals

Taking a fractal view of lean can provide a helpful framework for applying lean thinking at different scales.

Organisation

The organisation itself can be considered a lean fractal. This fractal is particularly important as it provides the environment in which other lean fractals will flourish or wither. Elements such as customer focus, leadership behaviours, skills development, structures, measures and rewards need to be designed and aligned to provide a supportive environment.

Value stream

A primary lean fractal is the Value Stream. This fractal includes all the steps and activities, usually involving multiple functions, required to flow value of a specific product or service to a customer. This fractal is highlighted by Womack and Jones in Lean Thinking in the second and third of their five principles of lean thinking: “2. Identify the entire value stream and 3. Make the value-creating steps for specific products flow continuously.” Many of the key lean tools are specifically targeted at this fractal such as Value Stream Mapping and lead time reduction.

Teams

Teams are a high potential fractal. Teams can apply lean thinking to many areas of their work that are within their gift to improve and at little or no cost. These include understanding who their customers are – external and internal – and what they want; monitoring and handling incoming demand volumes and variations; up skilling, cross skilling and capacity balancing to handle demand; root cause problem solving and visual management. These lean practices typically cost less, rather than more, and generate significant wins in productivity and quality. They simply represent a more intelligent way for teams to work, to self-organise and self-optimise.

Another helpful fractal is inter-team improvements between two teams. Many business issues and, conversely, opportunities for improvement, lie in the poor interaction between two teams. Sales think that credit is too slow and risk averse. Credit thinks that sales put revenue ahead of profitability. Business teams complain that IT takes too long to deliver new applications. IT complains that the business cannot say what it really wants.

Two highly effective lean methods for inter-team problem resolution are Kaizen workouts and A3 root cause problem solving. Both represent a rapid and structured approach to mobilising the right multi-function change team, understanding the root causes of problems, and developing and implementing appropriate solutions.

Practical Implications of a Fractal View of Lean

For an organisation deciding to take a fractal view of lean the implications are practical and potentially far reaching. Consider Broccoli again:

| Zooming in … | Or zooming out … |

|

|

Every bud is involved in making the whole. In other words, a fractal view of lean suggests that everyone is involved. There is no part of the organisation that is outside or excluded from the fractal.

Engagement

A simple way to engage everyone is to propose that every member of the organisation becomes, at the minimum, lean aware and familiar with the basic concepts of customer purpose, value versus non-value work, waste and flow.

For example, the Lean Competency System (LCS) Level 1A certification is a good way to enable and track this objective. This can be accomplished through a short training course, often using a fun simulation such as the Lego Game, or there are short lean eLearning courses available that give Level 1A Accreditation on passing an on-line exam at the end of the course. As well as developing learning, the external LCS accreditation and the recognition involved generates positive people engagement.

Leadership

A fractal view of lean also suggests that leaders at every level need to know their part in creating a culture of continuous improvement. This can start with a one day lean leadership course which teaches simple behaviours that have immediate impact.

For example, joining daily team huddles to understand what’s happening on the ground; asking direct reports “what waste am I driving and what can I do differently to remove it?” and sponsoring the use of A3’s and root cause problem solving as everyday habitual ways to resolve issues. In the words of one COO, “we want to create a culture where not everything has to be a project to get fixed!”

Enterprise wide

A fractal view of lean supports the notion that every part and level of the organisation can benefit from lean thinking. This can be particularly helpful for functions that have typically fallen outside lean focus areas, such as legal services or compliance. These functions tend to see their work as so specialist that lean cannot be applied. Yet the benefits can be significant. Legal and compliance activities are usually part of, and influence, multiple core value streams such as sales, services and customer on-boarding.

Having these specialist areas understands who their customers are, internal and external, what they want, the volumes and variations of work involved and how to process and capacity balance as effectively as possible can be a great competitive advantage, as well as making work a lot less stressful for everyone involved.

Individual level

A fractal view of lean promotes a new focus on each of us as individuals. How can lean thinking help us improve and enhance our personal ways of working? No one enjoys the constant stress, juggling acts and overcapacity that are part of today’s working landscape; lean, surely, can help and it may also be that focusing at the individual level can have a profound impact at the system level.

Consider this case. In a workshop for the Lean Centre of Excellence for a global energy company, a plan for deployment of lean across the organisation was being developed. One member of the team remarked: “you know what would make the biggest difference of all – and it’s not even on the plan: if we just had a culture of people doing what they said they would do!”

There was a powerful simplicity in this observation and it was evident that there was considerable waste and cost in accepting this behaviour as the cultural norm. For example, non-value adding meeting time, missed plans and unpredictable performance. While those present agreed with the sentiment, it was not addressed in the plans. The lean perspective was too focused on value streams and teams to be able to adapt to this more personal and individual form of waste. A fractal view of lean, arguably, could have helped in this situation.

Issue resolution & problem solving

A fractal view of lean would promote the use of a range of simple improvement roadmaps that people can use to address different types of business issues: resolving issues within the team; enabling two teams to work better together; dealing with a short sharp tactical problem; streamlining a value stream of activities across multiple functions. The power of these roadmaps is not that they are the perfect way or even the mandated way – but that they are a standard starting point for people to use and adapt to resolve problems as fast and effectively as possible. People can decide how to and where to drive the improvement train, but they don’t have to build the railway tracks each time!

This idea is developed by Ravindranath Pandian in A Simple Path to Excellence: A Body of Knowledge (Pandian, 2016). Pandian simplifies improvement to the two categories of Thinking and Doing. Within each category are Books of Knowledge or BoKs. For example, within the Doing category are three BoKs for addressing Simple Problems, Well Defined Problems and Ill Defined Problems. Pandian proposes the concept of Excellence Fractals:

“Each BoK composition would serve as a fractal, a scaled version of the total. The fractal composition of BoK can dramatically vary in depth, breadth and complexity. Our suggestion is to use the most minimal composition to address a give environment. The gaps, if any, can be eminently filled intuitively by human agents, the unseen force in this BoK. Instead of prescribing comprehensive tools for every circumstance, this BoK seeks to provide directions for every problem environment. Human agents are waiting for directions and can synthesise their own tools.” (Pandian, 2016)

Summary

Just as the broccoli is a never ending pattern repeating itself at different scales so a fractal view of lean involves everyone in the organisation creating a culture of continuous improvement at every scale. A fractal view of lean brings together and make sense of the multiple flavours of improvement methodologies.

Although it is made by repeating a simple process, Romanesco broccoli is actually very complex containing no fewer than four vitamins and twelve elements including manganese, calcium and selenium. Likewise however many elements form part of a fractal lean culture, the underlying process is very simple: to continually and repeatedly flow more value for less resource. Fractal lean, like the Romanesco broccoli, can be endlessly nourishing, nutritious and healthy at every level.

![]() Download a PDF version of this article

Download a PDF version of this article

References

Allen, D., 2001. Getting Things Done. 1st ed. London: Piatkus Books.

Fractal-Foundation, 2015. What is a Fractal?. [Online]

Available at: http://fractalfoundation.org/fractivities/WhatIsaFractal-1pager.pdf

[Accessed 29 November 2015].

Gunther, S., 2014. Mother Nature Network: 14 Amazing Fractals Found In Nature. [Online]

Available at: http://www.mnn.com/earth-matters/wilderness-resources/blogs/14-amazing-fractals-found-in-nature

[Accessed 17 July 2016].

Hines, et al, 2004. Learning to Evolve – A Review of Contemporary Lean Thinking. International Journal of Operations and Production Management , 24(xxx), pp. 4-15.

Jones, W. a., 2003. Lean Thinking – Banish waste and create wealth in your corporation. 2nd ed. London: Simon & Schuster.

Markovitz, D., 2011. A Factory of One. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

McNally, J., 2008. Wired Magazine: Earth’s Most Stunning Natural Fractal Patterns. [Online]

Available at: http://www.wired.com/2010/09/fractal-patterns-in-nature/

[Accessed 17 July 2016].

Pandian, R., 2016. simple-path-excellence-MEGAPHONE_ARTICLE_POST. [Online]

Available at: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/simple-path-excellence-body-knowledge-enterprise-ravindranath-pandian?trk=hb_ntf_MEGAPHONE_ARTICLE_POST

[Accessed 13 November 2016].

The Five Key Components of Sustainability?

At the 2016 PEX & Performance Management Europe conference in Amsterdam, we ran an ‘interactive discussion group’ on the key enablers of sustainability. Participants were given 24 cards, each containing a potential sustainability enabler, that they had to rank in order importance. Sustainability was defined as when new ways of working and improved outcomes become the norm.

In the feedback session they then had to group them into categories and decide on the key components of sustainability that should guide them and inform their approach when implementing lean oriented change.

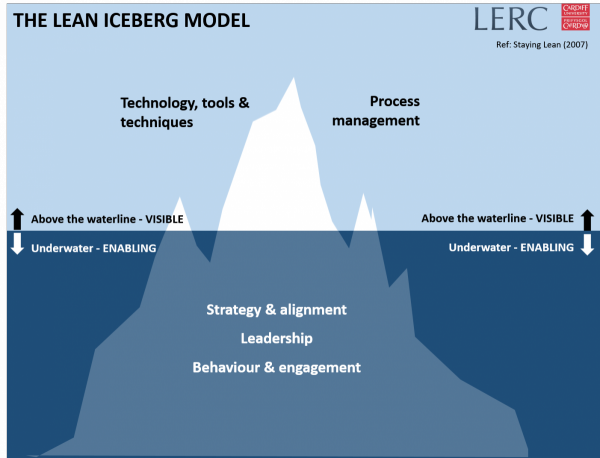

Their conclusions were compared to the list on a card that had been prepared beforehand (illustrated above) on which we had listed our five key components of sustainability – distilled from a variety of studies and research on the topic.

Not surprisingly (and just as well), the group’s deliberations did align very closely to the card, with the main conclusion being the critical importance on the people and leadership – or soft – factors.

We referenced the Lean Iceberg Model during the feedback session and discussed the importance of focusing on the enabling factors at the same time as using the tools and techniques to improve processes if sustainable change was to be achieved..

We referenced the Lean Iceberg Model during the feedback session and discussed the importance of focusing on the enabling factors at the same time as using the tools and techniques to improve processes if sustainable change was to be achieved..

The credit card sized list was given as a workshop take-away, hopefully to serve as a colourful, visual reminder and prompt.

Reducing the list to only five words is attractive in terms of memorability and simplicity, though whether these particular five words are the best ones is arguable and while there is no right or wrong answer, it would be interesting to get other’s thoughts on the five words they would choose.

A learning from the session is that these days lean managers and practitioners are very much aware that you have to get the enabling – ‘beneath the waterline’ factors right if you want to succeed with and sustain change. Having the right words that clarify and direct is, of course, just the first step – and being able turn those words into deeds is the real challenge!

Leveraging Lean for a More Environmentally Friendly Business

Due to the growing pressures on businesses to take a much greener approach, many companies are finding additional resources to help them become more environmentally friendly. Implementing a lean strategy, however, can actually help businesses to become eco-friendly organically without the need for significant investment.

Central to the lean approach is to cut out unnecessary waste in processes and refine operations so they focus on activities that add value for the customer. This often includes tackling aspects such as energy, power, pollution and environmental waste and streamlining these areas will have a very positive impact on the environment and will immediately result organisations becoming greener.

Aside from being better for the environment, there are actually several business advantages to becoming a greener company. Here are a few ways that using lean to become eco-friendlier will help improve your results.

1. It can save you money

The costs of running a business are constantly increasing due to the rising prices of materials and customer demand for lower prices. That is why more and more companies are adopting a lean approach, to help them cut out money-wasting processes and save on unnecessary spending. Operations that include excessive consumption, energy and waste are often the first to target, therefore saving your business real cash, whilst also delivering a more positive impact on the environment.

2. Going green is good for business marketing

Promoting yourself as a green company adds to your business’s brand value. Consumers are often discouraged by companies with a reputation of being wasteful and will actively seek out those who promote a positive environmental message. Lean businesses are already well-known for being more environmentally friendly and are therefore in a good position to promote a positive environmental message to other businesses. Not only is this a good way to generate more exposure for your business but it also helps to build a positive reputation for your brand.

3. Attract higher quality employees

According to a recent survey, eight in ten employees would rather work for an environmentally ethical organisation. The increase in global environmental concern has encouraged a shift in career priorities, with more people looking for jobs that make a difference, as well as just an income. Being an environmentally conscious organisation will attract higher quality people to your company and therefore strengthen your business.

4. Get the edge over your competitors

Business in any industry is highly competitive, which is why organisations need to go the extra mile to get the edge over their competitors. Showing your customers that you believe in more than just money is much more likely to get them to invest in you. By adopting lean, you are demonstrating to consumers that you are determined to impact the environment in a positive way, therefore encouraging customers to select you over other competitors.

5. Make your company more productive

Environmentally friendly organisations tend to adopt a more optimistic attitude, which has a knock-on effect of enhanced productivity. Many label this the “virtuous circle” as the positive efforts that go into making the company better for the environment has a direct influence on the productivity and motivation of the employees too. This generates an ongoing cycle of company efficiency and employee satisfaction, building a much stronger foundation for your business.

If you would like some more information on the positive effects of lean, take a look at our website: https://www.leancompetency.org/

Five Ways Lean Can Help You Get A Competitive Edge

Share this Image On Your Site

<p><strong>Please include attribution to https://www.leancompetency.org/ with this graphic.</strong><br /><br /><a href=’https://www.leancompetency.org/lcs-articles/five-ways-lean-can-help-get-competitive-edge/’><img src=’https://www.leancompetency.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/754px_5_Ways_Banner.jpg’ alt=’FIVE Ways Lean Can Help You Get’ width=’100%’ border=’0′ /></a></p>

By their nature all industries and sectors are competitive and in order to thrive, you need to get and stay ahead of your competitors. Lean helps businesses attain competitive advantage by identifying the key strategic areas for improvement and then optimising the processes of each. This enables them to become more effective and efficient, build credibility within the industry and gain market share.

1. Exceptional customer service

One of the biggest pitfalls for companies is poor customer service. Lean helps the firm to target and improve their customer service operations by cutting out ineffective processes such as customer waiting times and call transfers and focus on the things that add value. This creates a double advantage, as it not only builds up a positive customer experience but it also enhances your business reputation and brand, putting you in a stronger competitive position.

2. More value for consumers

Lean provides businesses with the means to generate more value for their customers. By removing wasteful operations and streamlining their approach, businesses are able to achieve high-quality results for their customers whilst simultaneously reducing running costs. This enables companies to provide valuable products or services to their customers at competitive prices.

3. High Quality Employees

Lean strives to help companies build a positive reputation, which is much more likely to attract high quality employees. Employing empowered, motivated staff with higher skill sets not only strengthens the business as a whole, but it also puts you in a much better position to challenge major competitors.

4. Business growth

For companies to compete in a congested marketplace, they need to be constantly improving the weaker aspects of their business and innovating to create new or improved products. The lean approach focuses on constantly revisiting all processes in order to enhance them and help the business improve and grow. This puts you in a strong position to compete with other businesses.

5. Positive environmental impact

By cutting out physical waste in processes, lean naturally helps companies to become more environmentally friendly. With huge pressures currently on businesses to put forward a positive environmental message, promoting yourself as a green business can provide you with a significant advantage over your competitors.

If you would like more insight into how lean can help your business stay ahead of its competitors, Lean Competency System can tell you all you need to know. Simply get in touch via the website.

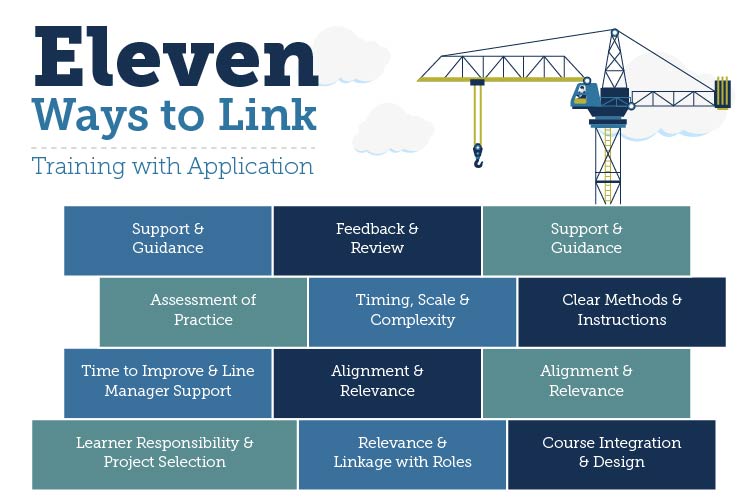

Eleven Ways to Link Training with Application

Share this Image On Your Site

<p><strong>Please include attribution to https://www.leancompetency.org/ with this graphic.</strong><br /><br /><a href=’https://www.leancompetency.org/lcs-articles/11-ways-link-training-application/’><img src=’https://www.leancompetency.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/754px_11_Ways_Banner.jpg’ alt=’Eleven Ways to Link Training with Application’ width=’100%’ border=’0′ /></a></p>

Learning by Doing

“For the things we have to learn before we can do them, we learn by doing them.”

― Aristotle, The Nicomachean Ethics

Linking lean training to the application of knowledge in the workplace is critical if it is to be considered effective in generating an acceptable return on investment, engendering real business benefits and playing a positive role in the development of a continuous improvement culture.

It is particularly important for those new to lean methods and continuous improvement in general, though should be a feature of lean oriented education at any level.

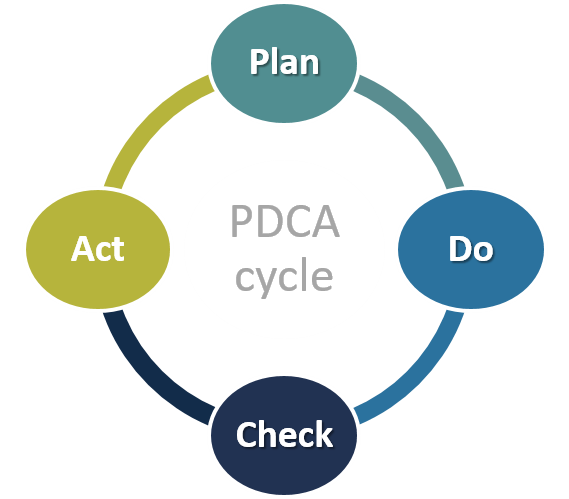

Most lean practitioners realise that while training should provide a strong technical foundation and structure for competence development, more extensive learning and mastery of lean tools and techniques can only take place through ongoing application, utilising scientific thinking and the classic PDCA approach. Hence learning by doing, or experiential learning, is seen as central to lean competency development.

Most lean practitioners realise that while training should provide a strong technical foundation and structure for competence development, more extensive learning and mastery of lean tools and techniques can only take place through ongoing application, utilising scientific thinking and the classic PDCA approach. Hence learning by doing, or experiential learning, is seen as central to lean competency development.

This is a key reason why the LCS defines lean ‘competency’ as having both knowing and practice elements.

Training Effectiveness

This links with the broader topic of measuring training effectiveness and there have been numerous studies into this area that should be referenced when considering how to assess training’s impact.

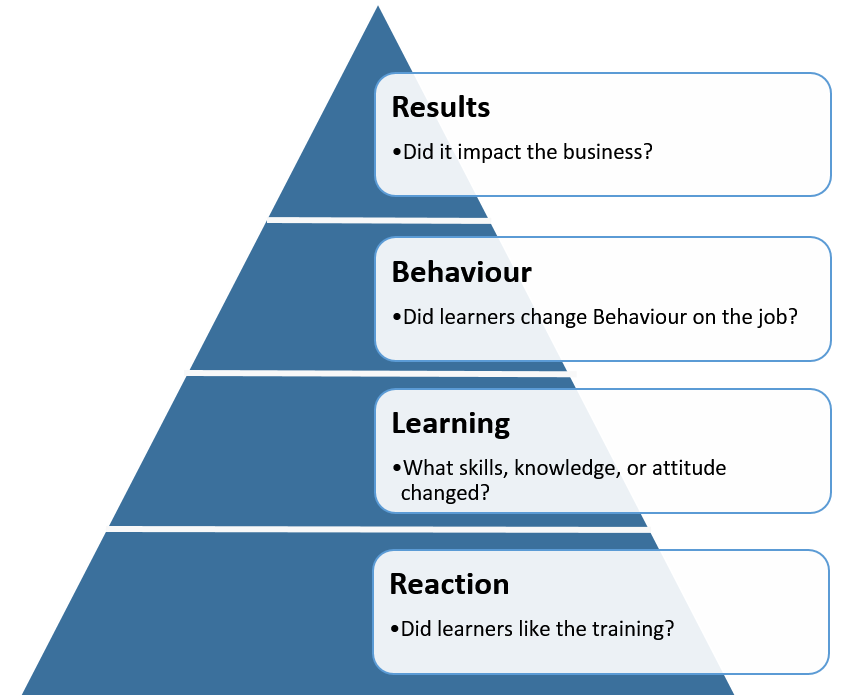

Several models and approaches have emerged, the most famous of which is probably the Kirkpatrick Model followed by Kaufman’s Five Levels of Evaluation. [see Kirkpatrick Model infographic].

Training Challenge

On a practical level, some CI managers report challenges in getting those trained to apply their new knowledge in the workplace, for example by undertaking post-course implementation projects and, not surprisingly, fear that the impact and effectiveness of the training will not be fully realised if this does not take place.

A general assumption, of course, is that learners will be applying their new knowledge in a working environment that is supportive of continuous improvement; if it is not, then clearly there is a risk that improvement activity never gets very far off the ground in the first place.

The Eleven Factors

Below is a list of factors that can play a positive role in ensuring that implementation activity follows a training course or programme. These have been gathered from observation and feedback and it is by no means a definitive list, so it is likely that additions or refinements can made.

Which are pertinent to an organisation will depend on a number of considerations, such as the organisation size, its geographical footprint, the level of formality of its overall CI approach and the particular model adopted, its level of lean maturity, how it resources its lean support function, in-house or consultancy delivered training and so on.

1. Course Integration & Design

A fundamental factor – and probably the most obvious – is to ensure that theory and practice are closely integrated when designing the course, which is likely to be the case if it is a subset of the organisation’s overall business improvement strategy. Expectations that the knowledge gained should be implemented relatively quickly should also be established early on and reflected in the course objectives, learning outcomes and delivery approach.

A fundamental factor – and probably the most obvious – is to ensure that theory and practice are closely integrated when designing the course, which is likely to be the case if it is a subset of the organisation’s overall business improvement strategy. Expectations that the knowledge gained should be implemented relatively quickly should also be established early on and reflected in the course objectives, learning outcomes and delivery approach.

There should be mechanisms in place to promote this, for example

- Having a training programme spread over a period of time, with ‘homework’ between each training session involving a practical task which is subsequently reviewed in course sessions.

- Having specific discussions about implementation methods and ideas during the course.

- Requesting that learners arrive at the course pre-armed with ideas for implementation projects, preferably gathered from their colleagues or managers.

- Discussing the post-course implementation aspect with relevant stakeholders before the course takes place to gain buy-in and elicit improvement ideas.

2. Relevance & Linkage with Roles

Training must appear relevant to learners and closely linked to their ‘day jobs’ and work priorities, with obvious opportunities apparent for implementation. Course material should include pertinent case studies and examples based on similar industries or from previous organisational improvements that learners can relate to. Having some training sessions actually on the ‘shop floor’ can be valuable, though this may not always be easy to organise.

Training must appear relevant to learners and closely linked to their ‘day jobs’ and work priorities, with obvious opportunities apparent for implementation. Course material should include pertinent case studies and examples based on similar industries or from previous organisational improvements that learners can relate to. Having some training sessions actually on the ‘shop floor’ can be valuable, though this may not always be easy to organise.

Training can be made more relevant and better received when delivered by a teacher or facilitator with authoritative practical experience, as well as subject matter expertise.

Linkage with roles can also be enhanced if CI is part of job descriptions and relevance can be magnified if expected outputs are well aligned to business goals (see below). Similarly, if CI is included in the organisation’s appraisal or personal development review processes, then it will be higher up personal agendas.

3. Learner Responsibility & Project Selection

The course selection or admissions process can impact the success to which knowledge is applied in the workplace, as in a recent research study by Ashridge Business School it was found that learner individual characteristics was the strongest predictor of the transfer of knowledge in the workplace (compared to programme design and work environment). Therefore, it is critical that participants possess the appropriate knowledge, skills and attitudes to learn and transfer what is being taught – and this aspect can be emphasised in the course itself.

The course selection or admissions process can impact the success to which knowledge is applied in the workplace, as in a recent research study by Ashridge Business School it was found that learner individual characteristics was the strongest predictor of the transfer of knowledge in the workplace (compared to programme design and work environment). Therefore, it is critical that participants possess the appropriate knowledge, skills and attitudes to learn and transfer what is being taught – and this aspect can be emphasised in the course itself.

The research also concluded that participants need to ensure they are clear about the benefits of the programme and should identify ways to apply learning to their roles, taking personal responsibility for applying that learning back in the workplace, as well as seeking feedback regarding new skills.

As suggested in 1) above, care needs to be taken in identifying the project or activity that the learner will eventually undertake in the workplace, given the importance of personal responsibility in its success. Selection criteria can be established and a degree of rigour exercised in identifying projects so that the learner is committed and feels real ownership.

4. Support & Guidance

Providing guidance, coaching and support to learners when undertaking post course implementation activities is vital, especially for novices. Ideally, experienced practitioners should be available locally to assist in this task, which could be in the form of the local CI team, a lean support office, external consultants or simply experienced colleagues.

Providing guidance, coaching and support to learners when undertaking post course implementation activities is vital, especially for novices. Ideally, experienced practitioners should be available locally to assist in this task, which could be in the form of the local CI team, a lean support office, external consultants or simply experienced colleagues.

There may be a particular challenge where practitioners are geographically dispersed and isolated, in which case more creative solutions may be required. Digital communication technologies have a role to play here, such as web based services, for example, Skype for Business, WebEx, Google Circles etc., as well as social media, blogs and discussion forums on intranets or public platforms. Web based library resources can also be a valuable asset. Also, undertaking improvement activity as a local group or part of a team can help mitigate the problems of geographical isolation.

Support and guidance also includes capturing data on learners progress, as there will need to be monitoring and probably some chasing, as invariably a marshalling role is required. Finally, whatever support is offered, it should be easy to access and responsive when called upon.

5. Feedback & Review

![]() Linked to Support and Guidance, there should be opportunities for periodic review of work undertaken to deal with any issues that arise. This could take place within the context of a training programme using a teach-apply-review approach, or part of a scheduled reporting or feedback routine.

Linked to Support and Guidance, there should be opportunities for periodic review of work undertaken to deal with any issues that arise. This could take place within the context of a training programme using a teach-apply-review approach, or part of a scheduled reporting or feedback routine.

These can take place through a combination of physical and web based meetings, if the IT infrastructure allows, while the web versions are invaluable for those in remote locations. These activities ensure regular communication takes place, create continuity, help maintain momentum, as well as keep up interest.

Peer review is particularly effective in generative constructive criticism and also can create a sense of problem/solution ownership by the group.

6. Clear Methods & Instructions

Learners should be clear on what methods and techniques they will be using for their implementation activities and how they report and communicate the results of their activities. The training should have described precisely the organisation’s improvement model and approach (if present), the standard analysis and improvement tools to be employed, the problems solving methods used, the communication processes and so on.

Learners should be clear on what methods and techniques they will be using for their implementation activities and how they report and communicate the results of their activities. The training should have described precisely the organisation’s improvement model and approach (if present), the standard analysis and improvement tools to be employed, the problems solving methods used, the communication processes and so on.

The organisation should also have its own standard analysis and reporting mechanisms, such as A3 templates, project charters, report formats and templates, easily assessed and available physically or digitally in a resources library.

7. Assessment of Practice

Ensuring that the training’s assessment strategy includes a practical element clearly signals its importance to learners and knowing that a failure to complete this part will result in not passing the assessment should act as a positive motivator to finish the task.

Ensuring that the training’s assessment strategy includes a practical element clearly signals its importance to learners and knowing that a failure to complete this part will result in not passing the assessment should act as a positive motivator to finish the task.

Learners should be clear on the criteria to be used to assess projects and different elements can be weighed according the importance attributed to each.

Where there is also a knowledge test as part to the assessment, the two parts can be weighted differently – for example, 60% in favour of a project and 40% in favour of a test. Again, this emphasises the relative importance of implementation.

8. Timing, Scale & Complexity

Have a reasonably short a time gap between the end of the training programme and the expected delivery of an improvement project report will help it remain alive and salient. This suggests that projects should be appropriately scaled and do-able within the short time period, so should not be overly complex or involving a high number of stakeholders, departments or complex value streams.

Have a reasonably short a time gap between the end of the training programme and the expected delivery of an improvement project report will help it remain alive and salient. This suggests that projects should be appropriately scaled and do-able within the short time period, so should not be overly complex or involving a high number of stakeholders, departments or complex value streams.

The length of this time gap will depend on the experience of those being trained, with a shorter period of around one month for newcomers and up to six months for others.

For those new to improvement practice, initial implementation experiences are as much about building confidence and learning about how to use tools and techniques as they are about delivering business benefits, so a more relaxed view can be taken on aspects such as strategic impact and hard quantified returns.

9. Time to Improve & Line Manager Support

If continuous improvement activity is not an explicit part of role or job descriptions (and it not often is), those responsible for managing the training need to ensure that the learners line management support the post course activities and sanction the appropriate time to undertake the work. Having the project linked to local priorities should help in this, as will pre-course stakeholder consultation.

If continuous improvement activity is not an explicit part of role or job descriptions (and it not often is), those responsible for managing the training need to ensure that the learners line management support the post course activities and sanction the appropriate time to undertake the work. Having the project linked to local priorities should help in this, as will pre-course stakeholder consultation.

Of course, allowing employees time to be creative or innovative is not a new idea – for example, 3M’s famous “15 percent time,” programme, that allowed employees to use a portion of their paid time to pursue their own ideas, which is fêted to have led to the development of some the company’s great products.

Having the support of line management will depend significantly on the overall state of CI in the organisation as a whole. Line managers in organisations with established CI cultures and habits are clearly more likely to offer support compared to those where lean’s acceptance and practice is more varied in its different units or divisions, where middle management may not fully understand or champion lean principles.

10. Alignment & Relevance

Implementation activity and improvement  projects need to be seen as pertinent, timely and fitting, relating to business unit or departmental purpose/goals and local KPI’s. This increases the chance that stakeholders take them seriously, as they can have an impact on key metrics and personal performance.

projects need to be seen as pertinent, timely and fitting, relating to business unit or departmental purpose/goals and local KPI’s. This increases the chance that stakeholders take them seriously, as they can have an impact on key metrics and personal performance.

Post course improvement projects should clearly state up front the benefits they aim to bring to the organisation, usually under the Quality-Cost-Delivery banner. While hard financial outputs are often demanded from an improvement project in the form of costs saved, a more balanced scorecard approach is preferable – perhaps focusing on releasing capacity, new sales, customer value, environment, health and safety, morale and other soft factors that have a more indirect positive contribution.

This non-cost reduction focus may be necessary for novices and will also help in reinforcing the message that real lean is not about cutting costs.

11. Reward & Recognition

Reward and recognition has a role to play in incentivising learners to apply their knowledge and one of the LCS’s underlying premises is that the external acknowledgement of achievement can play a powerful role in motivating employees to engage in continuous improvement.

Reward and recognition has a role to play in incentivising learners to apply their knowledge and one of the LCS’s underlying premises is that the external acknowledgement of achievement can play a powerful role in motivating employees to engage in continuous improvement.

Motivating learners is critical and recognising that you need to appeal to self-interest and address the “what’s in it for me?” question that is sub-consciously asked by many. Recognition for achievement will address the esteem needs of the Maslow motivation model – the need for appreciation and respect.

Formal recognition for successfully completing projects (and other aspects of the assessment) can be achieved by certification and qualification awards, which can be trumpeted and heralded through award presentation ceremonies, internal PR stories showcasing success and prizes for best project or best team, etc. Celebrating success also helps build teams and the right corps d’esprit.

Article Download

Download a PDF version of the article

Eleven Factors Linking Training with Application