The Habits of an Improver by Prof Bill Lucas

Introduction

It can be argued that the effectiveness of lean thinking in the workplace is ultimately due to individual behaviour and motivation – and on the critical habits that people form that are conducive to process thinking and continuous improvement.

In this Healthcare Foundation article, Prof Bill Lucas of the University of Winchester argues that if we can clearly articulate the of range habits which improvers need to have, and the knowledge and skills which will help them improve services, we can more precisely specify the learning required and the best learning methods, which will enable educators better understand the teaching and learning methods which best develop these habits.

At the same time, there is a need to make people see improvement not as an event or a ‘project’, but rather as a way of working, which will involve practitioners having to learn and, most importantly, unlearn behaviours.

While the article has a specific healthcare focus, its thinking has universal application across all sectors.

Peer to Peer Learning

Introduction

Learning is undergoing some big changes and several educational commentators are predicting that the future of learning will be dramatically different with factors like global connectivity, smart machines and new media reshaping how we think about work, what constitutes work and how we learn and develop the skills to work in the future.

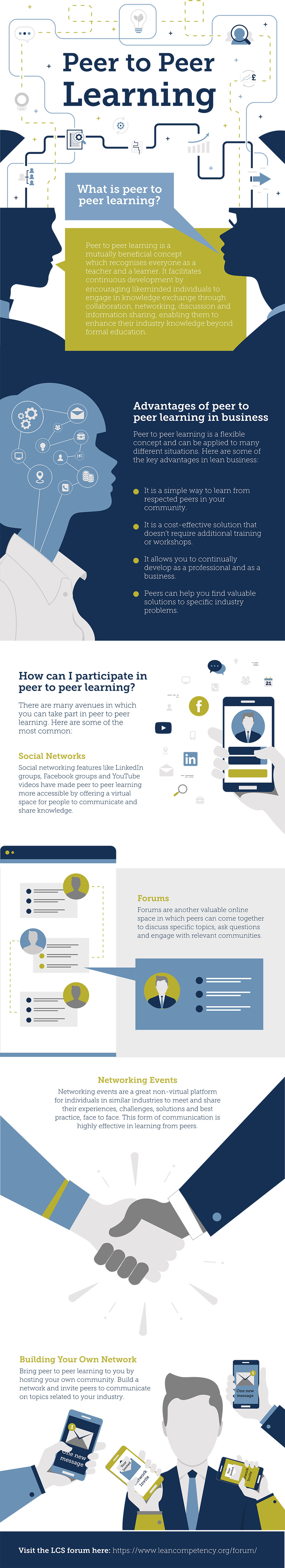

Fuelled by these trends, the importance of peer to peer learning is set to increase, a point highlighted in the 2017 Trends in Learning study by the Open University’s Institute of Educational Technology, which included learning from the crowd and learning through social media as two of six key trends in learning, both of which are integral to peer to peer learning.

This article defines peer to peer learning, lists its advantages and discusses participation options, highlighting the LCS Forum’s role in providing a digital space for the lean community.

Share this Image On Your Site

<p><strong>Please include attribution to leancompetency.org with this graphic.</strong></p>

<p><a href='https://www.leancompetency.org/lcs-articles/peer-peer-learning/'><img src='https://www.leancompetency.org/wp-content/uploads/Lean-Peer-to-Peer-Learning.jpg' alt='peer to peer learning' width='1000px' border='0' /></a></p>

What is Peer to Peer Learning?

Peer to peer learning is a mutually beneficial activity which recognises everyone as a teacher and a learner. It facilitates continuous development by encouraging like-minded individuals to engage in knowledge exchange through collaboration, networking, discussion and information sharing, enabling them to enhance their industry knowledge beyond formal education.

Peer to Peer Learning & Continuous Improvement

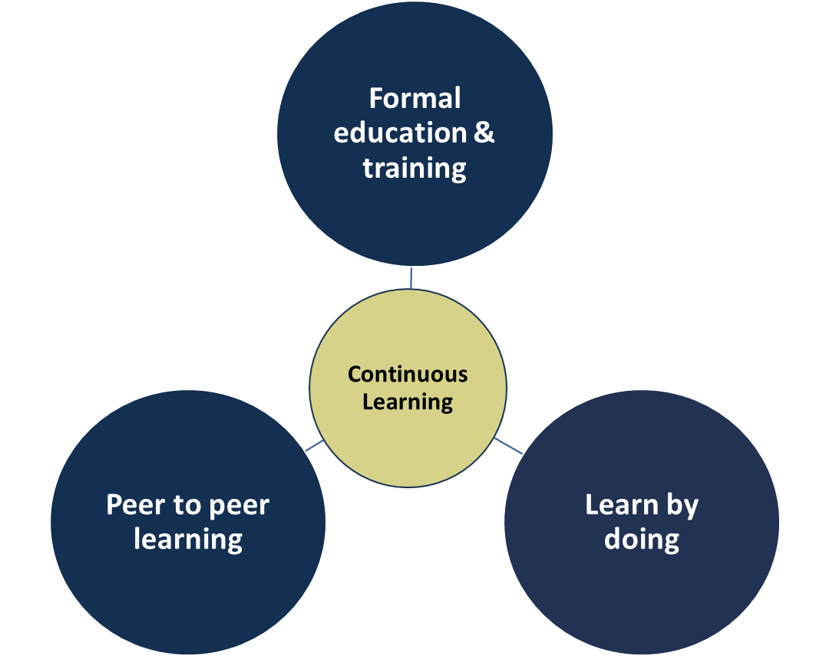

Continuous improvement, it can be argued, requires continuous learning, which can most effectively be achieved by blending three different ways of learning, as illustrated:

Formal education and training, typically classroom based – though increasingly online or blended, has an important role in introducing core concepts and ideas, ensuring understanding and enabling group participative learning via simulations, games and case studies. Formal training should provide confidence for learners to apply their newly gained knowledge in the workplace, often with support initially.

Learning by doing is a term often used to describe experiential learning, which is essentially learning through reflection on doing, which becomes the bedrock of ongoing competency development.

The third element, peer to peer learning supports and complements formal learning and learning by doing. It is less structured and formal and can take place in many contexts.

The growth of the use of the web and social media in particular means that virtual peer to peer learning is set to become increasingly important in the future. Indeed, some argue that a majority of learning takes the form of informal knowledge sharing in a peer-to-peer setting.

Advantages of Peer to Peer Learning in Business

Peer to peer learning is a flexible concept and can be applied to many different situations. Here are some of the key benefits for a lean oriented organisation:

- It is a simple way to learn from respected peers in your community.

- It is a cost-effective solution that doesn’t require additional training or workshops.

- It is a highly effective method of sharing information and people can learn real-life, applicable lessons from subject matter experts from all around the world, particularly when utilising web and e-learning resources.

- It allows you to continually develop as a professional and it promotes the learning organisation.

- Peers can help you find valuable solutions to specific industry problems.

How Can I Participate in Peer to Peer Learning?

There are many avenues in which you can take part in peer to peer learning. Here are some of the most common:

Social Networks

The nature of social media is inherently suited to peer-to-peer learning and social networking features like LinkedIn groups, Facebook groups and YouTube videos have made peer to peer learning more accessible by offering a virtual space for people to communicate and share knowledge.

Forums

Forums are another valuable online space in which peers can come together to discuss specific topics, ask questions and engage with relevant communities. Your organisation may have its own internal social media platform and the LCS Forum provides digital space for knowledge exchange amongst peers on subjects relating to lean.

Networking Events

Networking events are a great non-virtual platform for individuals in similar fields to meet and share their experiences, challenges, solutions and best

practice, in a face to face environment. This form of communication is highly effective in learning from peers.

Building Your Own Network

Bring peer to peer learning to you by hosting your own community. Build a network and invite peers to communicate on topics related to your industry.

How to set up a private community on LCS

- Register on the LCS forum

- Contact: membership@leancompetency.org with your private forum topic

- Provide a list of email addresses including people you would like to invite to the forum

A Strength Based Approach to Lean

Introduction

Never before has there been such a strong call for a culture of continuous improvement in the private and public sectors across the global economy. In these challenging times the appetite to discover how to do this better has never been greater.

Process improvement has been developed over the last 100 years and as a result, we know more about the challenges of implementing and sustaining a culture of continuous improvement across organisations than ever before.

These challenges are particularly apparent when trying to expand continuous improvement initiatives or projects to a complete culture across organisations so that continuous improvement becomes the ‘way work is done’. While Lean projects or short-term interventions can be very successful in the short run, sustaining the improvements gained and instilling the values, ethos and culture of Lean Thinking is elusive and easy to miss.

Traditional Perspective

The traditional view is that the best method for improving the way processes in our organisations work is to understand in great detail what does not work well at present. The next step is to find a solution to the problem or its root cause, and finally to implement it.

We were also taught to develop a vision about a desired future state (typically based on ‘best practices’) for our processes – followed by a focus on bridging the gaps between the ‘as is’ and the desired ‘to be’ states. Both approaches create a continuous focus on the gaps, inadequacies and weaknesses of our processes, systems and people.

Admittedly, these approaches to organisational change and improvement have served us fairly well over many decades by driving significantly greater efficiency and quality in manufacturing and other processes. However, there are well-documented examples of failures in driving improvement culture. For example, even the Toyota Motor Company, the source of the Toyota Production System (TPS) which laid the foundations to many of the principles and tools in the Lean toolbox, has experienced several highly-publicized challenges in recent years that exposed weaknesses and inconsistencies in the way its TPS philosophy was implemented.

These included a well-publicized slow response to the discovery of defective car parts installed in millions of cars around the world, as well as other glitches in its supply chain and customer service. These experiences exposed difficulties in truly responding to customer demand on time, in contradiction to the well-known principle of ‘Just in Time’. This example is given not in order to pick at Toyota specifically (it is still an inspiring example of success) but rather to demonstrate how challenging it can be to instil a true and sustainable culture of continuous improvement.

Strength-Based Lean: A Different Way

Most applications of Lean Thinking begin with an assumption that there is a theoretical ‘perfect state’ for each organisational process, and that the current state deviates from the ‘perfect state’ due to inefficiencies and waste.

This starting point means that, in order to improve our processes, we have to focus on the identification of gaps between the current state and the desired/perfect state (this is called ‘deficit focus’). Finding root causes for these gaps and fixing them follows next. At best, this approach takes you back to a state of status quo (‘good’) where expectations are met but rarely exceeded. It is unlikely to help us exceed customers’ expectations (‘great’)

The strength-based approach to Lean has a different focus. Instead of focusing on what is broken and inefficient, it teaches how to identify what is already working efficiently and generates value in existing processes and systems (this is called ‘strength focus’.) Next, we define ways to expand those parts and implement good practices elsewhere. This focus on the search for and growth of existing efficiency enables new ideas to emerge and supports implementation of process improvements by raising confidence, pride and energy levels.

The strength-based approach to Lean is more natural to work with and more sustainable in the long term. The focus of traditional Lean tends to weaken the system – even when it is successful – because it instils doubt and despair by giving unbalanced attention to waste and by amplifying inefficiencies.

In every organisation, there is a wealth of knowledge and practical experience about efficient and value-adding ways to work. The strength-based approach relies on existing good practices and internal knowledge rather than introducing ‘solutions from elsewhere’ thus making improvement easier. Visualise your teams as they discover the (often ignored) resources in their processes. As they do so, they find creative and energising ways to improve, truly moving from ‘good’ to ‘great’.

Strength-based Lean combines the rigour of Lean with the innovation and energy of Appreciative Inquiry and other strength-based approaches to organisational change, creating a more successful, inclusive and sustainable result.

Why Change Now?

We live in a world that is moving at great speed. The rate of change and innovation is faster than ever. There is simply no time to collect data, analyse it, identify root causes and fix them. By the time we have completed this cycle, reality will already have shifted and we are likely to find new problems. In addition, this fast pace also means that we struggle to sustain the improvements we were able to achieve or continuously drive the importance of waste and defect elimination. Motivation and energy – so essential for change – are likely to wane.

The alternative approach of bridging gaps does not offer a solution either. Focusing attention on external best practices, and on current gaps against those best practices, distracts staff attention and does not encourage engagement across the organisation or sustainability of existing good practices.

Strength Based Approach Benefits

A strength-based approach to Lean Thinking creates a committed and focused team working on an improvement initiative with a keen search for possibilities rather than problems. Observing any process with this different ‘lens’ invites them to start looking for the strengths and opportunities of the process, and to use this information to achieve the desired improvements confidently. Focusing on what works raises energy and motivation. Creativity is higher than that generated by following traditional improvement methods, and innovation is easier to achieve. The ideas for improvements generated through this approach are strong, as well as based on reality and knowledge from within the organisation.

Because the process of improvement is no longer accompanied by the negative feelings associated with waste and defects (even if this association is only implicit, it is always present with classic Lean Thinking), there is a higher degree of participant engagement and sustained energy towards improvement.

Leveraging current or past knowledge as well as accessing experiences and successes from within the system are a great resource for the next generation of improvement initiatives. They also provide motivation to everyone towards the challenges and opportunities ahead.

Teaching improvement teams and all members of the organisation how to find what is value-generating for customers drives them to consciously or unconsciously seek ways to deliver even more value to customers – isn’t that what we’re all about?

Robotics in Lean Financial Services: Friend or Foe?

Introduction

Growth of Lean in Financial Services

Lean’s application in services started to grow significantly in the early 2000’s, prompted by writers and practitioners, such as Michael L. George (‘Lean Six Sigma for Service’) and John Seddon (‘Freedom from Command & Control’) and Womack and Jones (‘Lean Solutions’).

In financial services, it was 2008 economic crisis that provided the real impetus for application, as companies were faced with reduced profit margins, increased competition and greater consumer demands.

Decidedly out of their comfort zones, and under pressure to develop and maintain comprehensive organisational processes, they had to consider substantial changes to the way they operated, requiring a deeper understanding of customer value and working out how these services could be optimised, delivering value for both the customer and the company.

Lean principles and methods seemed to offer a solution to the challenges faced. Profits could be improved by concentrating on services most valued by customers and costs minimised by eliminating non-adding value processes and operations.

Many financial institutions, it is argued, did not realise the full potential of Lean due to a singular focus on process redesign, rather than on a more systemic approach based around the development of a ‘Lean Management System’, central to which is an emphasis on people excellence. This encourages people to lead and contribute to their fullest potential, with robust structures to drive performance and the development of a culture of continuous improvement.

Pressures & Threats Maintained

The pressures and challenges facing Financial Services have not abated and indeed could be said to be intensifying. At the same time, emerging technologies and trends – such as robotic process automation, artificial intelligence, blockchain, big data – present significant opportunities and offer potential solutions to many of these challenges.

However, a key question to consider is how will these innovations impact on the Lean approaches now embedded in many financial services organisations and the integrity of the ‘Lean Management System’. Will they be disruptive and herald an abandonment of Lean ways of working or can they be complementary and integrate to create a more powerful force for operational effectiveness?

What is Robotics?

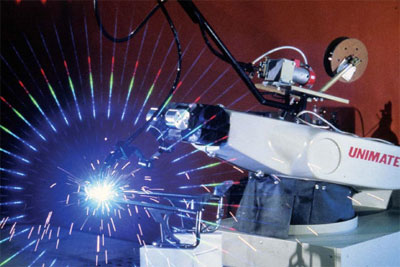

Robots are not new. In manufacturing, specifically automotive, factories first opened their doors to industrial robots in 1961, which is when Unimate joined the General Motors workforce. The Unimate robots boasted remarkable versatility for the time and could perform tasks that humans often found dangerous or boring and it could do them with consistent speed and precision.

Robots are not new. In manufacturing, specifically automotive, factories first opened their doors to industrial robots in 1961, which is when Unimate joined the General Motors workforce. The Unimate robots boasted remarkable versatility for the time and could perform tasks that humans often found dangerous or boring and it could do them with consistent speed and precision.

Ultimately, Unimate increased efficiency and eliminated further waste within the process manufacturing processes.

Automation and robots for manufacturing have come a long way since Unimate. The machines that manufacturers are using today are smaller, safer and able to perform more than a single task without expensive programming. While these innovations have significantly increased the value that automation brings to manufacturing, the latest innovations will transform the industry in ways that we have not seen since the first industrial revolution.

Just as industrial robots are now revolutionising manufacturing industries, Robotic Process Automation (RPA) “robots” are revolutionising the way we think about transforming business processes, IT support processes, workflow processes and back-office work. RPA offers dramatic improvements in accuracy and cycle time and increased productivity in transaction processing, while it elevates the nature of work by removing people from dull, repetitive tasks.

In Financial Services robotics does not, of course, involve the physical machines seen in manufacturing production lines; as the Institute for Robotic Process Automation and Artificial Intelligence puts it, RPA ‘is the application of technology that allows employees in a company to configure computer software or a “robot” to capture and interpret existing applications for processing a transaction, manipulating data, triggering responses and communicating with other digital systems.’

Today, organisations continue to invest much time and effort into understanding and applying “systems that do,” such as RPA, but the real excitement is around what is coming next, as systems that “think and learn” become more prevalent.

Whereas RPA systems can work only with structured inputs and hard-coded business rules, the next level of automation — Systems that Think — can execute processes much more dynamically than the first horizon of automation technologies.

How is Robotics being executed?

Evidence suggests that organisations are spending significant sums to assess if RPA fits their business models and processes and there is no shortage of vendors which are promising attractive savings and results. However, the focus is heavily on processes and sections of the process in the back office.

Evidence suggests that organisations are spending significant sums to assess if RPA fits their business models and processes and there is no shortage of vendors which are promising attractive savings and results. However, the focus is heavily on processes and sections of the process in the back office.

It can be argued that to measure the predicted results from RPA, a Lean diagnostic should be carried out on customer journeys at the process level versus task to identify non-value adding activity. Once identified, waste can be removed through traditional Lean levers, automation and robots.

With such a great impact on the operating environment, there are questions on how we will interact with customers and how employees will carry out work. RPA has the potential to become a trusted and dependable partner, enhancing human capabilities and creating capacity to free people from routine work, empowering them to concentrate on more creative, value-added services. This is an important point especially in view of fears about intelligent machines substituting humans and taking jobs.

With any change initiative – whether IT related or not – success should be determined on how effectively it is adopted in the organisation. Robotics is no different.

Lean & Robots

At the recent Davos World Economic Forum, business leaders and politicians stated we are at the start of a technological revolution, with great predictions for the impact of RPA. Many believe that the financial services sector must adopt RPA, but the question remains: can Lean thinking and RPA work together – are they mutually exclusive?

Given, it is suggested, that true transformation in Financial Services has only been achieved through the adoption of a Lean Management System, robotics needs to be evaluated in the context of this system and its five key building blocks:

1. Vision & Strategy

Recently, financial institutions have taken advantage of shared services, process optimisation, outsourcing and offshoring to keep costs in check. Even with these changes, margins are still tight and few companies have good control of costs, where cost problems exist and how to manage them.

When starting a Lean transformation, it is very typical to find that departments or functions do not have a clear vision or strategy, with aligned business objectives top to bottom. They often have many approaches that are meant to reduce costs, but actually end up increasing them.

Aligning strategy and vision and business objectives with RPA will give greater transparency and provide management information that will allow better strategic decisions to be made. For example, the concept of the ‘no-shore’ could be an option, where work tasks are completed where they can deliver the greatest quality for the most appropriate balanced economic benefit to meet customers’ expectations. Without alignment to strategy and vision the full RPA benefit may not be maximised, similarly, without RPA and only Lean thinking, the full potential would also not be maximised.

2. Step Change

Using Value Stream Mapping to understand the front to back process allows work to be catalogued into two key categories of value add and non-value add. This enables an understanding of where the waste is the process and the use of traditional Lean tools, such as elimination, combining, rearranging, simplifying and standardising tasks.

When thinking about how RPA can be used, a mind-set of automating activities not jobs needs to be adopted. This allows the use of RPA as an additional tool to eliminate waste.

However, the same can also be true in that no robotic solution is by its own nature Lean. One aspect that often gets overlooked is that robotic systems can speed up the creation of waste and reduce profitability, if not designed into the total system properly.

Lean is thinking out of the box – removing time, effort, and cost from the processes. Robotic applications mean flexibility in design, and capabilities—not just motion. Designing Lean robotic applications can achieve ground-breaking solutions to ordinary tasks.

3. Continuously Improve

Customers’ expectations and demands continue to evolve; delighters soon become satisfiers and the process of switching to another financial institution is now simple and incentivised.

Sustainable change is one of the key success factors of any Lean transformation and a key to sustainability is the development of a continuous improvement culture. The financial institutions that have been most successful in applying Lean thinking have taken a systemic approach to continuous improvement, characterised by:

- Delivery Management: delivery against defined customer needs.

- Performance Management: providing transparency on current versus historic performance, thereby enabling management to set direction.

- Improvement Management: using root cause problem solving to close performance gaps and achieve target conditions

RPA will be like any other tool in the Lean toolkit – the only change will be in mindset moving from continuously improving to continuously innovating, whilst introducing an agile way of working to drive a problem-solving culture. The key is to use the end-to-end principle and problem solve in multidisciplinary teams to ensure that technical solutions are integrated into classic problem solving to open up different results along the customer journey.

4. People Excellence

“The brutal fact is that about 70% of all change initiatives fail.” (Beer and Nohria, 2000)

Why? Invariably because of poor buy-in of management and staff, where there is no change in mindsets and behaviours.

Most finance transactions are strictly rule-based by nature and the tasks involve large scale data entry and data validation – and this is the type of work at which robotics excels. In addition, robots can deliver great consistency, accuracy, auditability and speed, which are essential in financial services.

Repetitive mechanical and manual routines are not only time consuming, but also error-prone when performed by humans. These tasks tend to be tedious and demotivating too. RPA can free up team members time for more challenging, meaningful work and higher value tasks involving customer service and problem solving, for instance.

Will RPA reduce the change failure rate? No, not on its own.

The digital journey is seen to offer tangible benefits by business leaders and is being even more positively embraced by their employees. From new roles, different ways of organising work, and changing work practices there are significant opportunities to humanise work, as long as business leaders reinvent their people strategies, become digital role models building stronger interpersonal skills to have the confidence to inspire a more fluid, less structured workforce and to manage the introduction of new technologies.

Above all, business leaders will need to support their teams as they learn to work with robots and as robots learn to work with them. This will involve the creation of a Digital Workforce.

5. Business Excellence

Providing the structures for driving performance is critical, linking across the Lean Management System with Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) throughout the organisation. The key proviso is, of course, if you can’t measure, you can’t improve, resulting in the Lean Management System unable to operate.

Rather than relying on existing KPIs, the overall business strategy should be used as the starting point, which allows the identification of the key drivers of performance and operational indicators. Standard definitions need to be created and measurement across the organisation ensured, cascading at every level from top to bottom.

A guiding principle of all Lean transformations is to improve the flow of service delivery in order to drive business impact measured across key KPIs and enable cost reductions. Robotics can only add to the transparency and improve the overall reporting and governance system.

Conclusion

The financial services sector has seen significant change for around a decade, with unprecedented regulatory, customer and technology challenges and increased competition as well as economic and market instability.

The financial services sector has seen significant change for around a decade, with unprecedented regulatory, customer and technology challenges and increased competition as well as economic and market instability.

This is set to continue in 2017 and beyond, with the challenges of de-regulated banking rules, Brexit, the introduction of Challenger Banks and the Fintechs. Financial organisations will therefore need to look both inwards and outwards for ways to be efficient and effective.

It appears that the financial services industry is following a path similar to manufacturing with robotics, albeit several years later, but it is certain that robots are coming.

However, it is argued that Robotics alone will not achieve the benefits predicted, but neither can Lean alone meet the expectations of this demanding market. Robots needs to be viewed as an extension of Lean thinking, with the two toolkits integrated and working together, in order for success.

But a powerful toolkit is not enough and it is contended that for RPA to deliver real benefits it must be integrated into a Lean Management System. Managers need to build and foster a culture to continuously innovate, supported by an agile way of working, bringing the right people together to operate and problem solve. Without this innovate mindset, processes, services and products will not meet future customer expectations.

It is also maintained that we will need to change how we operate and interact on a day-to-day basis, with a true understanding of the customer journey being central. It means aligning front to back and re-skilling the human workforce at all levels to work alongside new technologies, ensuring they learn to work with robots and as robots learn to work with them.

This will result in the creation of a digital workforce and in this way, robots will enable a revolution in Lean.

![]() Download a PDF version of this article.

Download a PDF version of this article.

Creating Organisational Cultures of Learning – Linked Learning Loops

“The trouble with us is that we’ve got no corporate memory.”

I’ve heard this statement in various forms from a variety of different people I’ve worked with over the years. The starkest version came from a senior officer in a police force. He was referring to the fact that his organisation kept trying new improvement initiatives, which would never fully achieve their potential.

The projects made mistakes, progress stalled and the initiative would ultimately fade away into insignificance. Then, after a few years, something similar would be instigated, with no attempt to first understand why things didn’t work previously and put mechanisms in place to prevent them happening again.

A critical element of the problem is that even though an organisation keeps making the same mistakes that doesn’t mean its employees have forgotten what those errors were. As the senior officer recounted, he remembered what did and didn’t work – it was the organisation that didn’t. The ultimate result? A negative organisational culture hostile to change.

Many academics have sought to address this problem. Peter Senge, for example, in his book The Fifth Discipline highlights the importance of being a learning organisation. One that is constantly open to new ideas and innovation, and builds upon experience to become quicker, smarter and more knowledgeable. He suggests five different elements of a learning organisation:

- Systems thinking

- Personal mastery

- Mental models

- Building a shared vision

- Team learning

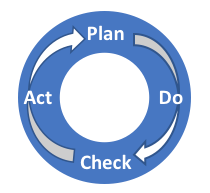

He is, of course, not the only voice to suggest that learning is key to success. W. Edwards Deming and Walter A. Shewhart introduced the ‘four-step management method’ to business in the early twentieth century. We can recognise this process as a ‘scientific’ approach to work.

- Plan: What do we want to change

- Do: Make the change

- Study/check: Did it achieve what we wanted?

- Act: If it did make sure that everyone benefits and embed the learning. If it didn’t, what should we try next time?

If discipline is applied to the process, the organisation ‘learns’.

Data is the key driver of this scientific process. Much of what many improvement methodologies offer, including Lean, Six Sigma and Agile, is mechanisms to collect, analyse and interpret information and data, so that managers can see what is happening, make a change and learn. Steven Spear and H. Kent Bowen are very specific about what this involves in their paper Decoding the DNA of the Toyota Production System. They talk about organisational learning taking place “at the lowest level” by those who do the work, under the guidance of a teacher, preferably using the Socratic method.

In my work, I see too many organisations that have put insufficient focus, effort, time and space into this learning process. The organisation understands (to varying degrees) that it needs to worry about its end-to-end processes and ultimately to keep improving them, but it often forgets about ‘creating an improvement process’ within which to examine the work process.

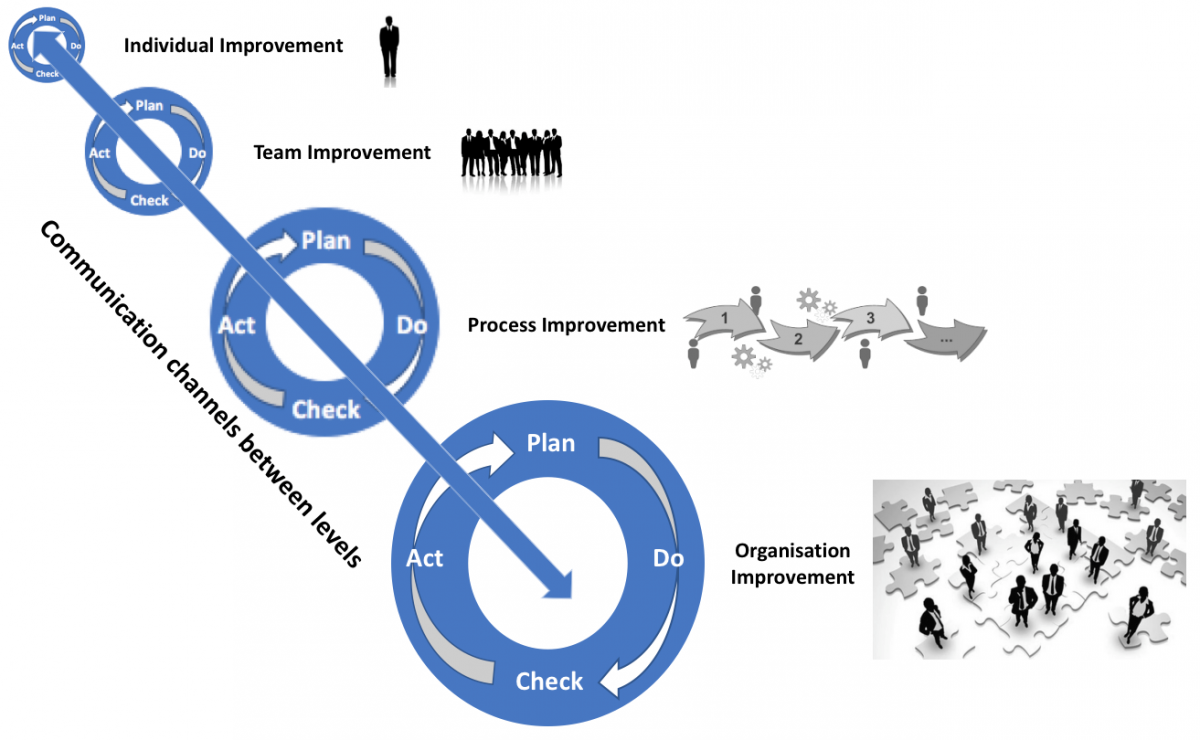

Critically, an improvement process is needed not only at a process level but at a team level, and even at an individual level. Above these levels of improvement, the organisation itself needs to examine how it works as a system, and improve how it sees and manages itself, how it learns.

I’ve tried to illustrate this concept in the graphic below, using the scientific ‘Plan, Do, Check, Act’ cycle as an iterative loop of learning, which must occur at different levels and scales.

What’s important is that there is a formalised improvement process for each of the levels. That each level is given time within their working day/week/month to engage in the improvement process and that they understand how to use the relevant improvement tools within each level. One of the most important features of this layered approach to organisational improvement is that there is an actual process of communication between the levels.

For example, if a team is experiencing difficulties with an element of work, then they should have the time and tools to scientifically work out what is going wrong and a communication channel to discuss problems with individuals. If, however, the trouble is occurring outside of the team, then they should know how to ‘kick up’ the investigation of that problem to the ‘process’ level. Too often improvement, and therefore learning, happens in isolation and not part of a connected system of organisational change.

Thinking about companies in this way enables managers to appreciate that it’s not enough to simply manage processes of work. They must also manage processes of improvement and learning.

This article originally featured on Hewlett Packard BVEX blog

Let’s Ban the Eighth Waste

From the Seven Wastes to the Multiple Wastes of Lean Thinking.

The Original Wastes

Taiichi Ohno famously identified the Seven Wastes of the Toyota Production System that have become part of the bedrock of lean knowledge and fundamental to lean improvement initiatives. Acronyms such as TIMWOOD regularly appear in handbooks and courses as useful ways to remember what they are: see Figure 1.

The Addition

However, many practitioners and organisations have added an eighth waste to Ohno’s original list, relating broadly to untapped human potential or some similar wording connecting to the notion that if you don’t maximise the contribution of employees and motivate them to excel, then this is ‘waste’ or at least opportunity lost. This often manifests itself in waste lists as:

- Non-utilised talent; under utilising peoples skills, talent and knowledge

- Not engaging all

- Intellect – not using employees intellectual contribution

- Mind (this allows an extra M in TIMMWOOD so it remains an acronym!)

- Skills – Under utilising capabilities, delegating tasks with inadequate training

- Creativity (lack of) or unused employee creativity

- Employee/people waste

Perhaps untapped potential is used in a lazy way to cater for many new or service related wastes and it even has its own acronym – DOWNTIME.

Why this has been added is probably to do with a lack of a human dimension in Taiichi’s original seven or maybe some feel compelled to be innovative or personalise the list in some way. But how useful and helpful is adding this particular ‘waste’ to the list and, indeed, is it actually a real waste?

What are Wastes?

Wastes were originally identified to be those activities that should be removed from the operation or process because they added no value for the customer; typically, they impeded flow, caused a problem and/or affected quality.

They were clearly identifiable, quantifiable and removable with consequent positive benefits to quality, cost or delivery. Part of their popularity and success was, arguably, due their simplicity in understanding and usability by anyone in the workplace.

As a way of emphasising the criticality of the waste reduction role, Womack and Jones, in the book Lean Thinking, refer to the muda glasses (muda being the Japanese word for waste) that lean thinkers metaphorically wear as they survey the workplace, imbuing them with special powers to spot non-value adding activities.

Does Unfulfilled Potential Fit?

So where does the waste of unfulfilled human potential fit in? Would you be able to spot it through those glasses, and if you were, could you then remove it and see an enhancement in customer value, better process flow or quality? Has anyone actually claimed that they have reduced untapped human potential from, say, 67% to 38%?

The answer is, of course, ‘no’ and it is nonsensical to suggest you could highlight it with a red Post-It on a brown paper map and then work out how to reduce or remove it.

Bigger Picture

Of course, people not fulfilling their potential is, in a sense, a waste of sorts, but so in that case is poor decision making, not being enthusiastic, daydreaming, having a bad education or a poor ability to concentrate and so on. Clearly, a manager or lean practitioner can do nothing immediate to improve someone’s ability to maximise his or her potential or talent in order to remove this ‘waste’, though no doubt education, mentoring, coaching or therapy could play a part in revitalising a person’s mojo.

Enabling employees to reach their potential is, arguably, a bigger organisational task and responsibility and many businesses would probably see this as part of their values or human resource management policies, rather than as simply a waste.

Issues

Does it do any harm adding it in? Including the waste of untapped human potential in the list raises several issues:

- It cannot be identified in a process or value stream.

- It cannot be readily be acted upon (and therefore is probably ignored).

- It can be distracting in the search for the real wastes.

- It devalues the wastes list.

- It positions untapped potential or talent in a negative context. The subject of realising potential or unearthing talent needs to be positioned as an opportunity and in a positive light, for example as part of personal development or education and training.

On this basis, untapped human potential does not warrant inclusion in a wastes list that is used to guide value stream improvements and so should be removed.

New Wastes

However, if this particular eighth waste should be removed from the list, it does not follow that the list should be permanently restricted to just seven; indeed, there’s a case that the list should have no particular limit.

John Bicheno has identified seven service wastes (see Figure 2) and John Seddon’s failure demand could be considered the arch-waste in many service environments.

In developed economies where about 80% of the workforce are employed in services, factors like the intangibility of the product offering and the customer journey are dominating features and digital delivery and communications are the norm. These open up a whole new world of wastes that could never have been on Ohno’s radar.

For example, we now have many different forms of communication wastes (eg excess, untimely, inaccurate), we are plagued with over-checking and over-authorising, we have poorly organised information on our hard drives, badly designed online forms, dysfunctional IT systems, unclear role definitions and targets that incentivise the wrong behaviours. Plus there is a range of environmental wastes that now need to be taken into account.

Developing Your Own Wastes List

If an organisation wants to be really effective in reducing wastes, it should develop its own list, relevant to its processes and products. Using the original seven is often a good starting point, as some are generic and have universal applicability, but not looking beyond them, renaming them or adapting them, may end up making the list restrictive, limiting waste reduction opportunities, especially in non-manufacturing contexts.

Also, shoe-horning in an original waste to your process environment – just to show it is somehow relevant – should be avoided; for example, in most services, it is impossible to over produce and put the resultant excess stock in a warehouse. However, you can, for example, deliver a service at the wrong time (the waste of untimely service) or have too many people involved in delivering it (the waste of over resourced delivery).

Waste Selection Criteria

In deciding what should be included in your own waste list, you should evaluate each waste candidate with the following questions:

- Does it add no value for the customer or stakeholder?

- Can to be removed or reduced?

- Does its existence impede process flow in some way either directly or indirectly or create inefficiencies?

- Is it quantifiable, so the benefit of its reduction can be measured?

- Can those working in the value stream, such as front line staff, have a role in identifying, reducing or eliminating it?

A yes answer to most of these will probably qualify it for inclusion in a waste list that is a real call to action, either as a non-value adding or a necessary non-value adding activity.

Summary

Ohno’s seven wastes are undoubtedly an important reference point in lean thinking, but they should not be treated as immutable or as a directive to blindly follow. Progressive lean thinkers have learned to adapt lean concepts and principles to fit their particular environments and the same is true of the wastes list, which should closely reflect the process environment so it remains actionable and relevant. So while untapped potential does not qualify to be on the list, there are multiple other candidates that do.