The Top Nine Productivity Myths

A never-ending stream of articles each offer a new answer for how to be productive — or the same answer, re-packaged in a new way. And yet, no matter how many articles we read, most of us feel stuck in our same bad habits. Some of the challenge is that it takes time to build habits that lead to greater productivity.

But a big part of the problem is that a lot of the advice out there just isn’t helpful — and can often be counter-productive. Here are nine of the top myths about productivity — pieces of common wisdom that it turns out don’t hold up, and may lead you astray.

Because we like to give you actionable information, we have also come up with alternatives that will help you stay productive — and sane!

Article author Elaine Meyer, published by Doist

Does Lean & Green Apply to Electronics Manufacturing?

A Gemba walk with Lean and Green glasses

Introduction

Although Lean and Green is a relatively new concept, the customary view is that it applies to “heavyweight” manufacturing. In other words, value streams that involve significant use of heating, cooling, power, chemicals, machining and large component manufacture. However, nearly everything we see, touch and use has electronic components in the background or at the user interface. So, can Lean and Green benefit this type of manufacturing which consists of green boards, miniature components and a bit of solder….?

Recently I had the opportunity to visit an electronics manufacturing factory. This site manufactures components for the various control and alarm systems for the automotive sector. The leadership team is considering applying for a Lean and green award. As result I had been invited to review the Lean and Green credentials of the site.

After an initial session understanding their products and manufacturing flows, we took a walk to the gemba to see the operations and review their lean deployment and their green deployment. The purpose, to see if they were both integrated into a single management system.

Gemba walk

The first area is the use of input resources and raw materials at the site. The main inputs from raw materials are: – blank green circuit boards, electronic components, solder, packaging and labels. The main environmental inputs are power, gas, chemicals and solvents.

The main processes are:

- Despatch area: All incoming raw materials were unpacked, re-packed and re-labelled to align with the internal systems.

- Manufacturing: Solder printing, automated pick and place assembly – the surface mounting of components, manual assembly of components, baking – although separate these processes all took place within one machine.

- Final assembly (covers and shrouds),

- Packing and store

After each step, the product is moved to test stations for quality testing. In between some of the processes, intermediate packaging is needed to protect the components from transit damage. A review of the factory performance showed a stable operational base. On time delivery, with high quality is the norm and not the exception.

Lean Deployment

Regarding Lean deployment, there were about half of the structures and systems in place that would support and sustain continuous improvement in manufacturing flow. Some continuous flow existed across the value streams. However, the cells appeared to be out of balance, with bottlenecks and activities starved of parts across manufacturing. Standard work is present and followed in some cells but not others, although this is a clear focus for leadership to improve.

Daily management system

An effective tiered daily management system is place across all operations. Cell morning-meetings (team leaders) are followed by a production morning (managers) meeting and then a cross functional leader site morning meeting. Visualisation is in place through electronic display systems, which allowed the display and interrogation of many KPIs and results.

However, as with all electronic systems, it did not promote continuous improvement through consensus or focus on the key problems for resolution. Engagement is limited to a discussion around the many graphs and tables and not on the actions to improve performance or resolve issues. In terms of the weekly continuous improvement time, none is provided or allocated to the cells or other teams. Continuous improvement time is ad-hoc and limited to completion of the spreadsheet of actions reviewed at the daily meetings.

Environmental performance

Environmental performance is driven through compliance and the enthusiasm and expertise of the local EHS manager. There is significant re-cycling of materials with a 10-way segregation – (although several containers had incorrect materials present showing poor source segregation in the factory). This is indicative of a compliance led approach to environmental deployment, effective management of materials and waste as well as some re-use of packaging materials. The site is not a heavy user of “E” flows (mass/energy/chemicals) – the main inputs centre around energy for automated component assembly and the oven.

Surprisingly, one of the other major inputs and outputs for production is packaging. Due to the sensitive nature of electronic components, every part arrived heavily protected with several layers of different types of packaging. Some of this is re-used in despatch or for intermediate transport within the factory, but the majority is either recycled externally or scrapped.

Contradictions?

Taking a step back and looking at the production area there are some environmental contradictions built into the factory system. There is an oven in the manufacturing area producing heat. However, here, cooling is required for the production process and to provide a comfortable ambient temperature for the working environment. The air conditioning required for production and an ambient working area is provided through nitrogen cooling. This produced a by-product of a cold air stream which is generated by the nitrogen transfer pipes and the natural thermic difference between warm and cold air.

However, this is situated outside of the factory so of no use internally. These major pieces of equipment are difficult to move but their positions and their impact on the energy demands of the site need to be added to the environmental mix.

External

Outside the factory, we took a walk to see the storage areas – the dark secrets of scrap, rework and waste are often hidden in corners of the yard. This is not the case for this factory. There is exemplary visual signage, waste and recycling segregation as well as secure areas for hazardous waste. The only opportunity is to investigate the contents of the containers that are used for landfill waste. Two a month were filled and on close inspection much of their contents should be re-used inside the factory or re-cycled.

Lean and Green integration

So, having taken a Lean and Green gemba walk around the factory, what are the opportunities for Lean and Green improvement?

Both the Lean and environmental streams of deployment have been deployed independently of each other. The Lean deployment has reached an intermediate stage of deployment which could be described as 2/5. There is some flow deployment and some of the required management systems in place. However, there is no employee involvement system and no practical visualisation systems in place. This means that any employee ideas did not have a route to get resolved. There is no time, structure, method nor leadership support system to enable employee involvement to work

The environmental systems deployment is a different story. It has been implemented to a very high standard and could be described as 4/5 for a factory of this type. The only areas for improvement are around packaging use/waste reduction and a reduction in the amount of waste going to landfill through better source segregation.

Summary

So, how would an integrated Lean and Green system benefit this electronics manufacturing factory?

Some way to go…

There is some way to go for this factory to achieve a level of Lean deployment. The cell, manager and leadership involvement systems although partly in place, need to be fully deployed. In addition, the work that has started on improving flow and reducing flow wastes in production needs to continue, to get to a level where the system supports continuous improvement. Once this system is mature – the employee involvement systems being key to the next steps, then the concept of the green wastes and green thinking can be introduced.

Cash savings?

The potential cash savings from improving the environmental diligence of the factory are not as significant as with other heavyweight manufacturing sites. The main operations consist of the assembly of small light products. There are no energy hungry processes like machining, casting, cutting and heating or cooling. However, the site services and packaging use are substantial environmental flows and the volume of packaging materials being sent to waste is significant.

Focus on environmental flow

The next stage for the factory is to focus on the environmental flow which was highlighted in the gemba walk – packaging. Using the Lean and Green Kaizen approach, getting together all the actors in this system in a workshop – supply chain, purchasing, logistics and manufacturing. The key objective to reduce or eliminate the volume of packaging. Analysis of value, data capture and investigation of use/recycle and waste of packaging products will surface the non-value attributes and provide a platform for improvement. These kinds of workshops also have a habit of seeding the organisation to grow in this direction.

Lean system improvement

Improving the Lean system will embed continuous improvement into the site and create a culture of solving problems to improve flow and reduce waste. Adding in “Green” after this level of maturity has been achieved for Lean will amplify the scope of improvement activities and create a culture of green improvement. In the past, the Green motivator for team members can exceed the profit motivator as it brings a wider aspect to the workplace – the environment.

Factories can be at different levels of maturity in both Lean deployment and green deployment. Typically, they are deployed on their own with Lean being driven from operations and environment being driven by compliance. Combined and working together will have a multiplier effect. The Environmental managers are often the lone promotor of environment in a site and gaining the support of operations through a Lean and Green initiative is a way to amplify the green activity and diversity Lean deployment.

More information

Playing with Operational Excellence

Introduction

For many people reading this, their experience of board-gaming will be limited to playing Monopoly or Cluedo; perhaps some might be chess players. However, over the last few years, particularly since the success of the game Settlers of Catan, there has been an explosion of ever more innovative board games aimed at adults, creating a strongly growing entertainment market.

If your experience of table top gaming ended with luck based, mass market games, you might be surprised to find that the hobbyist side is teeming with complex and deep games where players are invited to “engine build”; creating a process of taking actions that produce the greatest number of points for the least amount of investment. Often, this requires the player to not only improve steps within a system, but to design the end-to-end system itself. And many of the tools used in Lean can also be applied here.

Reducing Waste

In “deckbuilding” games such as Dominion and Artic Scavengers, players choose to add cards to a personal deck of cards, some of which are then drawn at the beginning of their turn and played to unlock actions and buy more cards. There will generally be a range of cards available to be added to your deck, cards will trade off between those that are worth points at the end of the game, and those that allow you to take powerful actions during the game. The challenge in the game is to create a deck that allows powerful actions, so that the player can then collect points.

The challenge of the deckbuilder genre is to reduce inventory waste. As the player collects cards into her deck, the chance that any one card will be drawn decreases. The successful player will be one that is selective in adding cards to their deck and prevents powerful actions getting lost amongst all the others. A powerful deck will allow for the most efficient cards to cycle into the player’s hand as often as possible.

As those cards that the player starts with, and those that award the most points generally have the weakest, or indeed no actions attached, their appearance in the player’s hand is similar to failure demand in a service environment. A wise player will not only aim to remove the weak starting cards as soon as possible to reduce the appearance of unwanted cards in their hand, but also delay the acquisition of point scoring cards, to prevent them reducing their opportunity to gain more at a later stage.

Improving Flow (Of Wine)

In Viticulture, participants run a vineyard in pre-industrial Tuscany, make wine which awards them points and income. An efficient player will optimise through-flow through their wine making “engine”, making sure the right grapes go into the press, in the right quantities and types to make wine, which meets the criteria of the contracts that they have been asked to fulfil. Further, a good player will attempt to keep a consistent flow. In order to win, players must always be in the process of growing, crushing and fermenting grapes; making the most efficient move at the most efficient time, players must reduce the non-value add movements and focus on delivering only moves that result in value (points)

Once a contract is fulfilled the player takes another, and then changes her production to meet this contract, therefore matching production to customer demand, and pulling on the production only that which is necessary. This requires players to create a flexible process capable of adapting quickly to the demands of the customer.

Systems Thinking

The economic strategy genre of games covers some of the weightier parts of the hobbyist board game market. These games tend to ask the players to manage some form or aspect of a business. From fast food chains (Food Chain Magnate), to shipping companies (Panamax) there is even a game called Kanban. Whilst many of these games reward aspects of management such as cash flow management and profit maximisation, and others, such as Arkwright, replicate macro-economics, several others invite the players to build a co-dependent system of businesses.

In Brass: Birmingham, players succeed by building primary industries that extract coal and iron that allow you to build secondary industry. This secondary industry then requires beer to begin production of manufactured goods. All of these resources will require the players to build a transport network across Birmingham and the Black Country to move to where they are needed.

As players can use each other’s coal, iron, beer and transport network, players must consider themselves in the wider system of the game. A player may choose to not invest in raw materials, but to use other player’s, perhaps a player will focus on building a transport network that will prove useful to others. And so not only must players think about their own end to end system and the interplay of their own resources, but also their place in the wider ecosystem of the game, positioning themselves to be efficient within that.

Implications for Operational Excellence Coaching

There is a growing understanding that games play an important part in the learning of individuals, and that the better the game, the more efficient the learning can be. In a Guardian article, the issue of poor quality games is discussed, and John Coveyou tells of his drive to found Genius Games, an endeavour to create games that educate people in stem subjects

Deming knew the power of using games to explain the principles of process improvement. In the red bead experiment, Deming would illustrate the frustrations and limitations of the traditional focus on individual performance and end of line quality. Here, he can take managers with decades of experience and force them to stand back, remove the complexity of the day-to-day of the modern corporation, and get them to see clearly the underlying themes and principles of traditional corporate practice. He is able to do this because humans use play to conceptualise and explore ideas.

In our roll-out of operational excellence waves we play games, following on from the work of Baringa Consultants, with whom we have been working, we play co-operative games that invite our training delegates to work together to improve a process.

Play is of undoubted value in a learning environment. Play allows training delegates to explore ideas and strategies in a risk-free environment and also impacts positively on the learning of these with a kinaesthetic learning style. Beyond that, it helps create a team atmosphere through common language and shared experience that is helpful at the beginning of an intervention of operational excellence.

While some people struggle to think of lean outside the context of their workplace, for many, the ability to explore ideas in new or different settings help them develop concepts further and relate to their own work in different ways. The playing of games can help training delegates encountering Lean concepts for the first time to “see the woods for the trees” on their own shop-floor. A well-designed game will also give immediate feedback that the player can intuit, that can be re-enforced by the trainer, allowing learning to happen on an instinctive and logical level at the same time.

Board games offer an OE Coach a collection of game mechanisms on which to draw, to create activities that can help their trainees explore and test lean concepts before applying their learning in the work environment.

Using the Power of TWI Job Relations

How to Overcome Engagement Stagnation and Accelerate Change: Using the Power of TWI Job Relations

Summary

In the second article on TWI, Denis Becker discusses how operations managers can build engagement and accelerate change by using the TWI Job Relations program. TWI JR develops our supervisors’ and managers’ Skill in Leading teams and fast, effective change. High Performance Supervisors know how to build and keep the trust and collaboration of their people. They make the TWI JR Foundations for Good Relations part of their daily work. They catch and solve people problems early, using the TWI-JR 4 Step Problem solving method. In short, they make people a key priority of their daily work. This creates happier and more productive employees and implementing changes becomes much easier and faster.

Introduction

Operations excellence is all about serving our customers better, and improving faster than our competitors. This requires us to build dynamic capability, that is the ability to handle change faster and more successfully than before. For any change to be successful, we need to bring our people with us. Strong engagement of front-line staff is, therefore, a critical ingredient of fast, sustainable process change. Without it, our progress will be slow and we will struggle to make changes stick.

TWI JOB RELATIONS helps our leaders build the level of trust and collaboration with front-line teams needed for successful continuous improvement. Success requires SKILL and WILL – they are like two sides of the same coin.

In my previous article I discussed how standardising work methods with the help of TWI Job Instruction accelerates lean transitions and boosts operating results.

TWI Job Relations cultivates the WILL. Together, TWI Job Instruction and Job Relations form a strong foundation for your operations excellence program, just as for the last 70 years they have done for Toyota.

Are we doing enough for employee engagement?

Nowadays most organisations regularly measure employee satisfaction and put annual plans in place, but find it hard to improve their scores. To overcome engagement stagnation and build dynamic capability to handle operations transformations and process changes faster, as operations managers we need to change the culture in our plants and offices. But how?

To build stronger engagement, supervisors and middle managers need to change the way they lead their teams. Actively working on building trust and collaboration needs to become part of their daily routines, alongside other tasks and habits that oil the wheels of production and customer service.

What kind of supervisor do we need?

A short while ago many of our team leaders and supervisors were our best operators. Promoting them from within makes a lot of sense, but it also creates challenges for our organisation and the new appointees. New team-leaders and supervisors must gain the acceptance of their old workmates in their new roles and learn to get results through other people. This is very different from just doing a good job on the process themselves. Not knowing how to make this transition is a key reason why many front-line leaders spend their days just keeping production moving, often by doing a lot of operator-level work themselves, rather than focusing their time and energy on building robust processes and self-reliant operating teams.

Being the boss is not enough, they must transition to becoming leaders.

In TWI JR we say that what makes a leader is having followers. People follow you because they trust you have their best interest at heart. Trust is hard to build and easily damaged. It requires consistency, daily effort, daily habits, constant reinforcement. If the necessary kind of routines for this to happen are not yet part of the DNA of your office or shop-floor, your supervisors need to figure out on their own how to organise themselves and how to lead. Some of them might do well, but many will struggle. As senior leaders, we must do better.

How can we help our supervisors and middle managers to become better leaders?

TWI Job Relations, a leadership skills development program created to teach supervisors how to build trust and collaboration and how to solve people problems sustainably, is a godsend to senior managers looking to improve the way their operations are run and their people are led. And it is a blessing for supervisors and managers who want to learn how to maximise their teams’ potential and improve performance.

In TWI JR we say that good relations give good results, poor relations give poor results. The TWI JR program teaches supervisors 4 Foundations for Good Relations, which they practise every day and which, over time, build trust and improve attitudes and relationships in their team.

TWI JR also provides supervisors with a practical 4 Step Method for solving people-problems when they do arise. By applying this pattern consistently to real-life problems in their daily work, they quickly get much faster and better at removing problems for good. They also learn how to spot and catch problems early, before they become big and tough to handle.

Leadership skills can be taught. Like all Training within Industry and Supervisor Academy training programs, TWI Job Relations is designed to build practical skills, through hands-on field application. By building real skills and daily routines, supervisors are able to immediately apply what they have learnt and generate ROTI (Return on Training Investment) for themselves and for your organisation.

Where can I get help with the skills transitions of my supervisors & middle managers?

The TWI Institute and its global partners, including the Supervisor Academy ®, develop the essential leadership skills and support companies all over the world in embedding these skills into their daily operations practices.

Our time-proven training programs develop not just awareness and knowledge but practical, hands-on skills that your front-line leaders apply straight away to generate hard, fast results and build long-lasting habits that transform their way of leading and working.

Find out what we can do to help you develop High-Performance Supervisors, by e-mailing us: info@supervisor-academy.org and visiting our Supervisor Academy and TWI Institute websites.

Succeeding with Work Method Standardisation: Using the Power of TWI Job Instruction

Training Within Industry

Training Within Industry – TWI – is often referred to as the forerunner of contemporary lean thinking and while developed in the US over 70 years ago to support the World War Two war effort, it is still practised by Toyota. In recent years there has been a renewed interest in TWI and a resurgence in the application of TWI methods in organisations, notably led by the TWI Institute.

TWI originally aimed to rapidly train and develop new staff in order to achieve an increase in productivity, quality and occupational safety. This programme included the development of three managerial skills, considered necessary for leaders and workers:

- The ability to instruct employees

- The ability to improve working methods

- The ability to build good relations with and lead employees

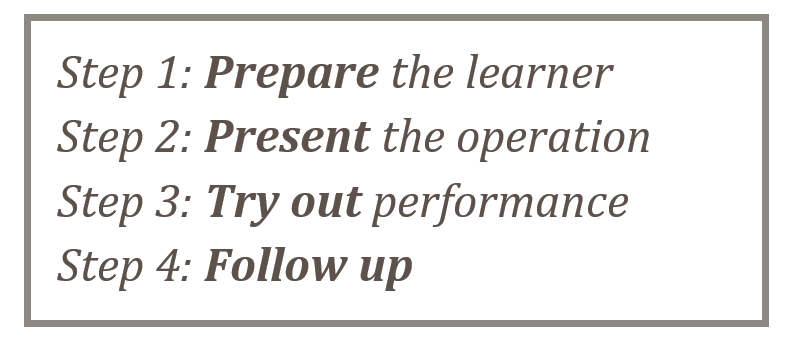

This article focuses on the Job Instruction element of TWI, which helps connect the written work standard with the actual practice on the shop floor and teaches the technique of delivering effective on-the-job training that ensures people reliably perform a task exactly the way it should be done to get consistently good results.

Introduction

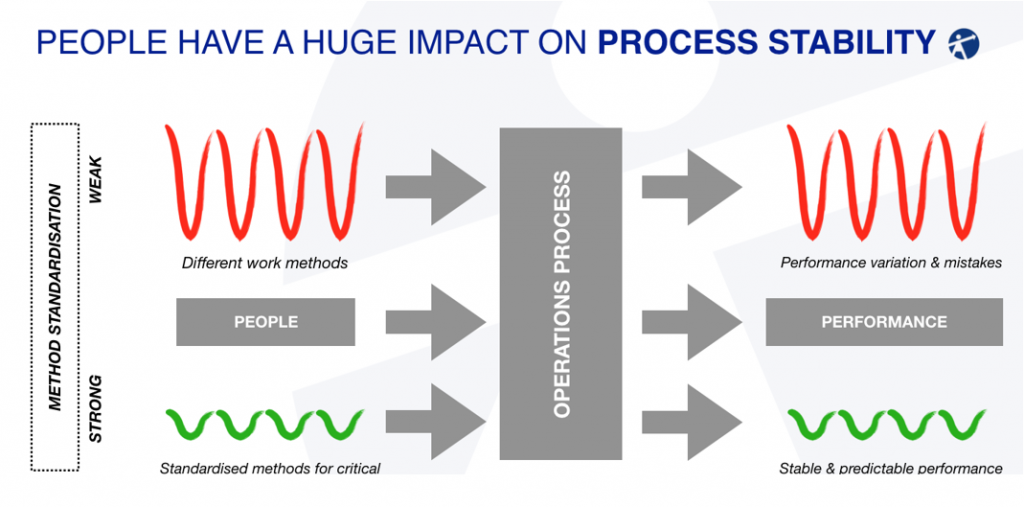

TWI Job Instruction is considered a key ingredient for successful operations excellence or lean programme. If people play a significant role in your processes, you will probably need to invest a lot of effort and resources on standardising the methods of how work is done, if you want your process improvement work to progress at speed and deliver results.

Most lean initiatives involve a lot of talk about the need to standardise work methods. Lean leaders realise that without ‘standardisation in place’, improvement won’t stick. Without standardisation, the new method you have just developed with your Kaizen team is just one of many, many ways of building your product or delivering your service. Without standardisation your process will deliver big variation in quality, output and time.

Therefore, standardisation is not just one of the things we ‘do’ as we strive for operations excellence. Rather, it should be the heart of our our operations excellence practice, the driver of improvement – not just the end result.

But despite knowing that standardisation is critical, leaders often struggle to do standardisation for real.

Are we doing enough work on standardisation?

As a result of ISO and other certification requirements, most businesses have work standards for their main processes defined on paper, including quality control plans, safety procedures, SOPs and work instructions.

But what we say we do and what actually happens on the process often does not quite match up. In many processes, people are still one of the most critical inputs. If you look at the detail in the Gemba, you will find plenty of differences in the way they do the work across shifts, lines and individuals. Variation in the way the work is done translates directly into output variation and mistakes. Squeezing method variation is therefore, arguably, the most important thing operations leaders can do to create stable, predictable process performance.

How can we bridge this gap?

Generally, work method variation can be traced back to faulty on-the-job training and follow up:

- Training content might not be specified enough,

- Training is too complex or delivered poorly.

- Follow up is difficult or not done.

This automatically leads to method variation on the process and affects outcomes. Therefore, if we want to standardise work methods, we need to improve the way we train and follow up on the training. We need a simple and reliable training system.

Training within Industry (TWI), a leadership skills programme developed over 70 years ago and still practised by Toyota, provides an answer. Its Job Instruction (TWI JI) program helps us connect the written work standard with the actual practice on the shop floor. JI teaches the technique of delivering effective on-the-job training that ensures people reliably perform a task exactly the way it should be done to get consistently good results.

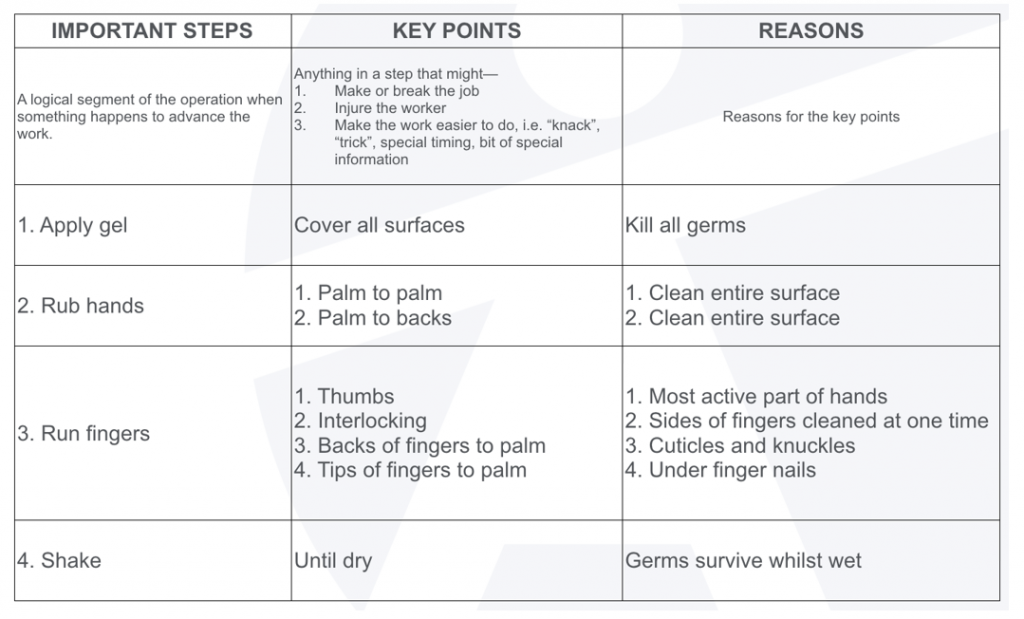

TWI JI specifies a simple, robust 4 Step method of training that raises our trainers’ training skill. It also provides a system for specifying training content in a way that ensures the critical aspects of each job are understood and practised reliably by trainers and trainees.

The Job Instruction Breakdown captures Important Steps, Key Points and Reasons for the key points – thus specifying clearly and succinctly the ‘best method we know today’ of performing a task.

TWI Job Instruction enables us to squeeze variation out of our training and follow up process, which leads to consistency in work methods applied in the Gemba. And consistent work methods reduce variability and mistakes.

How can I get my people to practice TWI Job Instruction?

Despite TWI JI’s apparent simplicity, businesses introducing TWI Job Instruction require good training and practice with coaching from an experienced practitioner to accelerate their learning curve and quickly get results from TWI.

TWI classes are standardised in content and schedule, and all aspiring TWI trainers go through a rigorous program of training and practice with the TWI Institute before achieving certification to train. This ensures the quality of training delivery and the necessary expertise to provide practical guidance as people start applying TWI on the shop-floor.

Whilst businesses generally start with external training provided by the TWI Institute or one of its authorised partners, after completion of the first successful pilot projects oftentimes they quickly move on to bringing the TWI training capability in-house by making use of the TWI Institute Train-the-Trainer program. This enables them to quickly train and involve a critical number of their staff in the program and, with this, consolidate TWI JI as the new method of on-the-job training and work-method standardisation.

Where can I find out more about TWI Job Instruction?

To find out more about TWI Job Instruction please visit the websites www.twi-institute.org & www.supervisor-academy.org

Economies of Scale vs. Economies of Flow

Introduction

Often when I’m teaching, I find myself skulking amongst the middle ground of contrasting ideas. Sometimes I’m even perilously perched atop of a massive fence dividing two opinions. Sometimes I’m in the middle ground of contrasting ideas, sat on the fence of indecision, whilst rocking back and forth muttering “it depends”.

I think that one of the strengths of a Business School such as ours is that within our teaching and research, we aren’t selling a solution, we present a range of different perspectives, from a position of impartiality, and, through critical evaluation, we enable our students and those we work with, to reach their own conclusions. Within my field of ‘Operations Management’ great spectrums of options exist and as leaders within complex organizational systems, I believe it is imperative to experiment to see which options are best employed when and where.

One of the most tense decisions as a leader, whether we recognize it or not, is deciding where our business needs to be on the spectrum between an Economies of Scale or an Economies of Flow approach.

Scale & Flow

Let me explain these two terms further. You are probably very aware of the term ‘Economies of Scale’. I think I even heard of it before I studied Economics A level. This term refers to the

“Financial advantages that a company gains when it produces large quantities of products”.

When you order in bulk, companies are more likely to offer discounts for example, offering a lower unit cost saving. When you are big enough, you can potentially buy a big machine to do the work for you, it’s probably a large initial outlay, but you are now making things in such quantity that the machine will ‘pay for itself’ soon enough, justifying its purchase.

The machine can do the task faster and more often and when you do the maths, you can now produce x many widgets at a fraction of the cost. Economies are achieved as you ‘scale up’ production. It could be said that Fordism was built upon this economic force. Workers were paid handsomely for their efforts, within a shorter working day, where they had to master a fraction of a complete task, which they repeated over and over again, generating huge economies of scale. Achieving the lowest unit cost of production is the primary goal. Within markets of huge demand, Economies of Scale are very powerful.

Economies of Flow aren’t nearly as concerned with money as their economies of scale opponent is. Speed is their primary goal. How responsive are we to the customer? How can we deliver something that the customer wants NOW? A helpful way to think about how Economies of Flow manifest themselves is by considering varying delivery charges. When companies are making regular deliveries to their stores, they’ll deliver your item to a store, for free, but you’ll have to go and pick it up. Not in a hurry and happy to wait 3-5 working days – 99p. Standard delivery £2.99, Priority service – one working day £6.99, Delivered within 4 hours by drone?! £45.99 (it will happen).

Pricing deliveries in this way is a mixture of attempting to change customer behaviour yes, but also as a consequence of the effort and actual cost spent in order to speed your delivery up above and beyond ‘usual channels’. Some of this is a fiction of course (second class mail often has to be deliberately delayed within the UK mail system for example), most of it is not. If we need more ‘little and often’ deliveries then we’ll need more people transporting things, which uses more fuel, which is more expensive – the customer needs to pay more if it wants this level of service.

Perhaps Economies of Scale are sounding more appealing at this point? Well again, I’d suggest caution here, particularly as within service organisations, we are often not making physical things, we are delivering ‘intangible’ solutions created through human relationships.

Demand variety & standards

John Seddon talks much about service organisations’ “ability to ‘absorb’ customer demand” – by this he means empowered employees, who possess the autonomy required to respond to customers’ requests, as and when they happen. Teams are multi-skilled and, contrary to the Fordist model where a worker learns a fraction of a total task and repeats it over and over again, they can adapt to customer requirements, applying sense, reason and intellect to the task at hand. Listening, identifying, helping the customer in front of them.

What often happens within centralized services, which again, might be a very good thing (gosh the world looks great from this aerial fence view!) is that standards become King. Work is rejected if it does not fit the brief. Responses are standardized and the ability to flex is greatly reduced. The realities of such factories of work is, if they are insufficiently designed and resourced, queues start to form. What’s worse is that these queues of work develop lives of their own. Employees shift from actually doing the task to managing the backlog. The backlog grows and grows as those within the queue repeat their request, adding a new work task to the mountainous heap (failure demand).

Another problem with centralized systems is the time it takes for work to actually get there. This problem is lessened within paperless processes, but when there are multiple stages of task, involving many ‘handoffs’ and permissions, the end to end delivery time can actually get worse. When coupled with the “centre’s” potential misreading of the customer requirement once it reaches them (because of their remoteness and distance from the initial demand), we can see that centralized solutions are somewhat losing their appeal.

Go with the flow?

This is perhaps where Economies of Flow have the edge. In the year 2018, customers want their items/service/solutions NOW and they want them to be RIGHT – this paradigm is not going to go anywhere anytime soon. Speed is often THE competitive advantage. It is unlikely that customers will desire a slower response, except if there are significant price savings and advantages to be had.

Summary

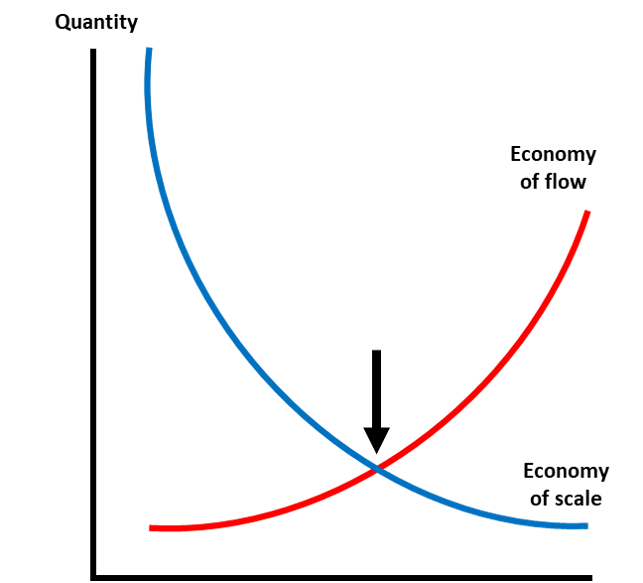

So what’s the answer? Well of course, it depends! Another colleague at Nestlé helped me think through this conundrum with the following graph. We can see here the financial unit cost advantages of an Economies of Scale approach, but also the increasing cost associated with a model focused on speed of delivery.

Organisations should seek to find the ‘sweet spot’ of the lowest unit cost Economy of Scale approach and the fastest possible ‘Economy of Flow’ approach. The reality is that this ‘sweet spot’ is much harder to find than the intersection of two theoretical lines on a graph!

I suppose I am going to challenge my own impartiality here and posit that more organisations need to prioritise the Economies of Flow approach as a successful mechanism to 1) win more work 2) secure customer loyalty and 3) deliver fantastic service experience. Localised teams who are multi skilled and are able to flex to meet customer requirement, owning end to end tasks, are desired by customers, and are immensely powerful within service systems.

One final thought – perhaps the graph sweet spot can be achieved through centralized IT systems that work, delivered through localized teams that listen?