Tesco: Lean Retailer Lost?

Co-written with Barry Evans and first published in February 2015

Introduction

Tesco has long been feted as a lean retailer and an early exponent of structured continuous improvement outside of manufacturing, so does its recent tribulations indicate that it has lost some of its lean sheen and indeed what does its experiences tell us about the nature of sustainable lean thinking in organisations?

Of course, Tesco is not the only retailer to be suffering, as in an apparent polarisation of retailing those in the middle market are feeling the squeeze – and recent consequences have included Morrison removing its chief executive and Sainsbury shedding 500 head office jobs. While Asda experienced its worst quarterly sales performance in at least 20 years in the 12 weeks to 4th January 2015, Aldi and Lidl increased sales by 22.6% and 15.1% respectively in the three months to January 2015 and Waitrose’s sales at established stores grew 2.8% in the five weeks to 3rd January, with grocery sales via Waitrose.com surging 26.3%.

While the UK grocery market is forecast to grow 16.3% from 2014 to 2019 (source: Institute of Grocery Distribution) key structural changes have been taking place and future growth will be driven by three principal areas: convenience, online and discounters. The shift in importance is illustrated strikingly in the table below, which shows the channel share of each £4 of market growth.

Channel Share of each £4 of market growth

Superstores and hypermarkets: -£0.42

Small supermarkets: £0.03

Other retailers:-£0.01

Convenience: £1.62

Discounters: £1.49

Online: £1.29

TOTAL £4.00

Being able to anticipate market tends and changes in customer value has been central to Tesco’s success over the last two decades, so has Tesco lost its ability to understand such shifts in market forces? It was the first major multiple to see the potential of two of these significant growth areas – namely convenience stores and online grocery sales and it began operating in these areas in late 1990’s. However, it appears not to have anticipated perhaps the most critical of these – the growth of discounting and associated changes in the consumer value proposition.

What Makes a Company Lean?

Unsurprisingly, there is no single measure that simply indicates that a company is, or is not, lean – not least because lean proponents have a variety of definitions of lean thinking which makes the task difficult.

However, what is generally accepted is that being lean is not about the propensity to use specific lean tools and techniques, the number of PDCA cycles undertaken or the number of CI experts or black belts employed, though these may be characteristics of lean companies. Measures of leanness surely must be expressed in terms of value and the ability of the company to deliver maximum customer value with the minimum resources, closely linked to its core purpose.

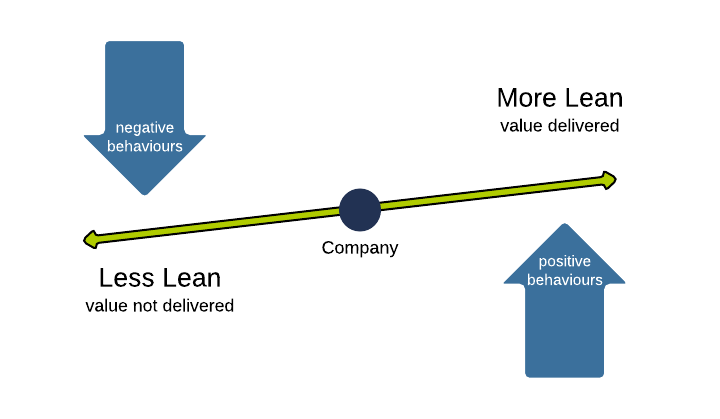

It is also helpful to view leanness not as an either-or condition, but rather as a spectrum or continuum, along which companies can move one way or another depending on their behaviours and performance in delivering value.

A key point to note about the spectrum is that it is lies at an angle, suggesting that a company will slide to the less-lean left if it does not maintain its ability to identify and deliver value and purposively adopt the right supporting behaviours.

Tesco’s lean credentials are evidenced by several factors. Driven by former chief executive Terry Leahy, it was an early adopter of lean thinking in the 1990’s, which was primarily focussed on cutting costs and removing waste from its supply chain, which lead to significant savings and improvements.

It pronounced that the seminal Womack & Jones book Lean Thinking was one of three that informed its mantra, along with Loyalty by Reichheld and Simplicity by de Bono. It adopted several lean techniques, notably the Tesco Steering Wheel as a policy deployment vehicle and perhaps most importantly developed a passion for driving customer value, illustrated by its better-simpler-cheaper test for any potential innovation or improvement.

However, its profitability, sales increase and market share growth over a prolonged period are arguably the critical indicators in its ability to deliver customer value and therefore meet the lean company test. From 1992 to 2011 its average annual profit growth was 12.5%, (which had slipped to -3.3% 2012 to 2014) with its comparative sales growth figures 12.3% and 1.5%.

Tesco, it is argued, has slid towards the less lean end of the spectrum, as it has become less effective in its ability to understand and deliver customer value. It has, not doubt, maintained lean activities, such as been taking waste out of processes, deploying strategy, improving flow and solving problems, though these alone are not enough to arrest the slide.

Tesco & Customer Value

Tesco under CEO’s MacLaurin and particularly Leahy had an excellent track record of working tirelessly to understand and deliver what customers valued. They developed many mechanisms to understand customer wants, such as Clubcard data, customer panels and market research.

Thus they strove to keep abreast of what customers wanted (or did not want) and crucially aimed to deliver this through focused company-wide change programmes, with all functions focused on what they had to do to deliver their part of it. No localised versions were permitted, but everyone was encouraged to feed in ideas for improvement – with the best chosen for development and company-wide roll-out.

These were evaluated and the best were developed into operable methods and implemented company wide. This delivered huge benefits, as each operation in distribution centre store order picking, store shelf replenishment, checkout scanning of customer baskets and so on is repeated literally millions of times each year, so a small improvement in each operation cascades through to significant bottom line gain. The better-simpler-cheaper failsafe ensured no unintended consequences, since improvements must have a positive impact on all three.

Of course, the delivery of customer value is very simple to describe, though not necessarily easy to deliver and making and keeping things simple takes hard, focused effort to deliver and sustain.

Factors Underlying Tesco’s Slide

The root causes of the decline in Tesco’s performance over the last two years and its ability to deliver value to customers are likely to be a combination of several factors, both external and internal. The relative importance of each is difficult to gauge and it is their interaction together that is important.

Externally, the financial crisis of 2008 had a negative impact on earnings and accelerated the rise of polarised custom – the discounters and high-end – which ushered a return to prominence of clear value propositions, such as promotions, and three-for-two, rather than an overemphasis on retail theatre. Changing consumer shopping habits, particularly the growth of online and convenience have also been important.

Internally, there are factors that may have contributed to losing sight of their customer. These include an over focus on technological changes and too much emphasis on extended supply chains, where low cost is chased through efficiency at the expense of effective provision of provenance and erosion of core values, which undermined customers’ trust. The horsemeat scandal was a case in point and the accounting issues and overstatement of profits a symptom of this malaise.

Terry Leahy warned in late the late 1990’s – the years of plenty – that Tesco’s biggest enemy was complacency. Being complacent, in lean terms, can be linked a loss of clarity of purpose, so did Tesco fall into this trap? With a high market share in a mature core home market, inevitably it began to look for other opportunities, to satisfy stakeholder demands for even more growth and bigger dividends and not least provide exciting new challenges for ambitious executives.

Consequently, there was diversification into a wide range of activities, including video-on-demand, financial services, brown and white goods, mobile phones, broadband and so on, as well as substantial international retail expansion. If you accept, as Disraeli said, that the secret to success is constancy of purpose, then the loss of clarity of purpose will inevitably lead a range of problems, not least in maintaining an understanding of customer value.

The Road to Lean Redemption?

The arrival of Dave Lewis, Tesco’s first ever externally recruited CEO in September 2014, has heralded a number of fundamental changes in direction. Under Lewis, who has a strong consumer brand pedigree, Tesco claims it will re-focus on what the customer values by taking it back to its core purpose and focusing on price, availability and service. It aimed to improve in store service by recruiting additional staff and has disposed of some of its technological offers.

Early indications of the impact of the new CEO’s approach on trading performance and share price have been positive and it is worth noting that Tesco’s financial performance is still delivering profits in excess of £1 billion – the only UK retailer achieving this – so the level of crisis is relative should be viewed in this context.

Summary

On one level, Tesco’s recent story can be part explained by a well-known marketing paradigm termed the Wheel of Retailing.

This contends that retailers enter the market at the low end and make immediate market share gains by offering low prices made possible by very efficient operations. Overtime, these retailers become increasingly bloated by letting their costs and margins increase. Their success leads them to upgrade their facilities and diversify, increasing their costs and forcing them to raise prices. Eventually, the new retailers become like those they replaced and the cycle begins again when still newer types of retail forms evolve with lower costs and prices. Loss of core purpose and lack of understanding of customer value lie at the heart of explaining the cycle.

Tesco under MacLaurin and Leahy were very successful and the latter’s obsessive focus on the customer and what they valued gave a powerful system purpose that Tesco followed. Many innovative changes were implemented and made possible by Tesco’s development of an increasingly capable supply chain.

At some point Tesco lost sight of the source of its growth, exacerbated by a number of self-induced and external factors including, a purpose that became more opaque and thus less meaningful, technology-based priorities seen as more important than delivering a customer service and possibly leadership complacency – deemed by Leahy to be Tesco’s greatest threat. In BBC Panorama programme in January 2015, Leahy said that he blamed poor leadership by his successors as the key factor, though it can be argued that several of the seeds were sewn during his tenure at the top.

Undoubtedly, the revolutionary market change driven by the financial crisis and the consequent market polarisation had a major impact that exacerbated the effect of the negative internal factors that resulted in the recent difficult years for Tesco. This is when significant changes in customer value occurred that, in fairness, were very difficult to predict.

The corporate graveyard is littered with the headstones of once great companies that, for whatever reason, at some point failed to deliver value to their customers and shuffled out of corporate existence. Sometimes this was due to internal factors or short product life cycles, sometimes due to external forces such as dramatic technological, social or economic changes.

Of course, it is notoriously hard to always know what customers want; three quarters of new products are said to fail, customers keep changing their expectations, they often do not know what that want and buy on emotion as well as reason. Henry Ford knew this when he said if I‘d asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.

The point is that occasionally companies will be faced with significant shifts in customer behaviour that they did not, or could not, predict. The ability to adapt to such changes is therefore critical to survival. This adaption will involve restating its purpose based around its core competences so as to engage with its customers and recapture the ability to understand value. The indications are that the new management at Tesco is returning to a customer-focused approach, getting back to basics and clarifying purpose. These, together with re-building positive behaviours, mean it has the opportunity to move it in the right direction along the lean spectrum and reconnect with its customers in delivering the value they demand.

Improving Customer Service through Digital Technologies: Learning from Different Sectors

A while ago, I wrote a blog about the role that digital technologies played when I bought a bike online and how important it was to analyse the entire customer experience when trying to ensure customer satisfaction. A key part of the great service experience in that example was the receipt of automated text messages which informed me about my order and when and where parts would be delivered. A friend recently told me about their experience when they moved house with Nationwide which surprisingly mirrored this experience. I was so pleased to hear that the digital method of keeping customers informed of the progress of the service requested, in this case a mortgage, had migrated to a new sector, that of financial services.

My friend received a text message at several stages of the process:

Text 1) To let her know that the mortgage product she had requested had been reserved and that they’d “be in touch again shortly”

Text 2) That the mortgage application has been received and that they’d let her know how the processes progresses

Text 3) That the mortgage valuation was booked, the date, and that they’d be in touch when they’d received the report

Text 4) That they had received a satisfactory valuation report

Text 5) That they were delighted to inform her that they had now issued a formal mortgage offer and that they look forward to completing on this offer (stages 1-5 happened within a week)

Text 6) That her solicitor had requested mortgage funds to be released by a certain completion date and if that date did not suit, then to please inform her solicitor.

This is seriously impressive not only from a speed perspective, but also from a customer satisfaction perspective. Buying a house is a worrying time, how reassured did my friend feel as she received text messages letting her know how things were going? These simple automated texts were, in a way helping her to feel more in control of a process that she actually, had very little control of. It also saved Nationwide work, she wasn’t ringing them every other day to check how her application was proceeding, or when the valuation was going to take place, automated text messages made the process transparent.

I’ve mentioned it before, but I believe that a key component of value within 21st century services is that of “visibility”. Customers want and need to know what’s happening. Digital technologies are a key enabler of visibility. They allow a customer to log on and see how things are going, to be informed about how their request is progressing, to make decisions about their services instantly, without having to rely on anyone else.

More and more, basic transactions are being placed in the hands of the customer themselves – the ability to self-serve. Think about how reliant we all used to be on visiting our local bank? Now I can do most transactions myself, I know what’s happening to my money as I can visit my account any time online, and I like it. It makes me feel in control.

There is no doubt that digital technologies can save time and effort within our processes, especially when these digital advancements gives the customer better visibility of what’s happening, and great control, customer satisfaction is enhanced. As we see such advances are moving through different sectors, organisations need to be aware that digital visibility will soon no longer be a delightful surprise, but a basic customer expectation.

The Destructive Force of the CAVE Mentality!

A regular criticism of a lean approach to work is simply that it’s “common sense”. If it’s so “common” however, then how come there are so many work processes that are so complicated, unwieldy and simply do not work?! To say that a lean approach to work is common sense belittles the amount of counter intuitive concepts that exist within the discipline. However, I’d be lying if I said that sometimes it can feel that all that is required in terms of intervention is an injection of a really strong work ethic and an overwhelming desire to improve!

A person who possesses both of these characteristics can be a formidable force within an organisation. The opposite of this, a person who has a CAVE mentality (that’s a Citizen Against Virtually Everything!), can be a hideously destructive force! When teaching, I show a great video “Building a Lean Culture” and the managers in the case study talk about how toxic people with a CAVE mentality can be stating that “they are the one bad apple that can spoil the whole barrel”.

Companies are increasingly putting more and more focus into ensuring that the staff that they employ are the right sort of people who possess not only the skills that they require, but also the right attitude towards work and improvement. Critically, these people need to be keen to learn and develop and are happy to contribute to the success of the organisation.

A trend that I’m currently noticing within operations management is that increasingly high tech companies such as Spotify, Netflix and Valve, are allowing their employees quite a bit of freedom in terms of the tasks that they work on and how they contribute to the company, allowing them the time and space to think innovatively and creatively. They are able to do this because they put a huge focus on a) recruiting the right people b) keeping the right people c) removing the wrong people.

Netflix are very clear in this now famous presentation, that they reward the best and do not tolerate mediocrity. Spotify are very clear about the numerous stages that you’ll need to pass through if you’re going to be allowed to join them.

Valve discuss how they have taken the time and trouble to find and recruit you as a new member of staff and as such, when you do join them, they’ll simply ‘let you get on with it’, finding a role for yourself to work on exciting new projects within an extremely flat organisational structure.

Successful organisations such as those mentioned understand that building their work on a strong foundation of amazing people is the most critical part of their operation. It is important to realise however that a bad organisational system, and encountering a few people with a CAVE mentality, can turn a potential shining star of an employee into an unappreciated, lethargic one. CAVE people have a habit of converting other people to the dark and dingy ways of CAVE life, so it’s not enough to take the time and trouble to hire brilliant, dynamic minds – organisations need to ensure that these minds are given the freedom to fly, are not brought down to earth by negativity too often, and feel supported by an organisation that truly values them.

Behold! Successful Government IT Projects!

There can be no doubt that there have been several high profile Government IT initiatives which have failed miserably. Attempts to upgrade and improve the NHS’s IT infrastructure were last year heralded as “one of the worst fiascos ever”. The abandoned scheme cost the taxpayer £9.8 billion pounds – a shocking waste of resource where all we can hope for is that some serious lessons were learned to never be repeated again.

However, there have been some really notable IT innovations within public service that are really making a difference. I’d like to celebrate a couple of those with you today to hopefully promote the huge power that IT innovation can make to help the country to run more efficiently and effectively.

The first initiative that I’d like to celebrate is GOV.UK – a truly impressive source of information which has been completely designed to meet the needs of the citizen and indeed, won the “Design of the Year” award in 2013.

A big problem within public service is the proliferation of information that exists about any of the thousands of services that a government provides, all of which can be exceptionally difficult for citizens to navigate. Can you imagine the levels of information that the UK Government is responsible for?! To aim to achieve a ‘one stop shop’ for citizens was a sizeable undertaking. GOV.UK has de-cluttered and simplified all of this information, conveying just the basics of what is required, all of which written in an easy to understand language. Try it out yourself and marvel at how within a few clicks, you can be effortlessly transported to essential information which answers your problem.

I had reason to use the website recently as I needed to change the address on my driving license. I reached the GOV.UK website by typing “change address driving license” in google and from that point, entered a process to really marvel at!

The first thing to note is the list of things ‘you’ll need to’ have or satisfy in order to be able to use the service, automatically making sure that those about to enter the process will be able to continue. When you “start now” you are taken through a series of screens which verify who you are (thanks to NI numbers, driving license numbers etc.) and from there you can then update your address. So far so good. I half expected to then be sent a printed application form in the post which I could then sign, attach a recent photo and return- the same process that occurs when applying for renewal of a passport (filling our your information online and receiving a printed, electronic copy to return sounds more expensive and more hassle, but actually ensures that you only fill out the information that is relevant to you and makes sure that you fill out all of the essential information thanks to “required fields”. It greatly simplifies the process whilst helping to guarantee that spellings are accurate – much better to type your details than for an officer to attempt to interpret potentially illegible written offerings!)

Imagine my surprise when the computer thanked me for my application and informed me that my new photo driving license would arrive shortly?! The driving license system was linked to the passport system and pulled my signature and photo from last year’s passport application. I was amazed! Sure enough, within 5 days a photo driving license, with my new correct address, arrived in the post. So easy! So effective! So little effort required from me!

In previous years, the Passport Service and the DVLA would have been very ‘separate’ institutions, the idea that these organisations ‘automatically talked to each other’, helping the citizen out by using information given to one in order to fulfil the requirements of another organisation, would have been almost inconceivable. Yet, when you think about it, it makes complete sense. The state knows what I look like, the state assures me of my citizenship and of my competence to drive, so the state should make it easy for me to prove both of these things. The whole process bore the hallmarks of ‘elegant simplicity’ and made paying my taxes, slightly more comfortable! A truly effective use of IT innovation within a public sector service.

Teaching Supermarkets: The Highs and Lows of the Board

When lecturing on the importance of the Board in determining the success of companies, the main company that I’d call upon to illustrate ‘how best to do it’ was Tesco. For years companies have been eager to hear about how Sir Terry Leahy, Tesco’s former CEO, used a balance scorecard to assess the healthiness of the business and how this scorecard was cascaded through the company via a mechanism called “strategy deployment”. This meant that key metrics flowed from the very top ‘Board’ level of the company, to the geographic region (e.g. UK, USA and South Korea), to the type of business (Tesco Express, Tesco Mobile etc.) to the individual store and individual distribution centre to the employee – aligning the company’s direction of travel – making sure that that direction was up. For 14 years, under Leahy’s leadership, this system was highly successful to the point where in the UK, £1 in every £7 was Tesco’s.

You would have to have been hiding in a bush for the last 12 months to not realize that these glory days have dramatically come to an end. Most mornings, as I eat my cereal, there’s another breakfast news story of doom about a Tesco scandal or the rise of Aldi and Lidl. That’s not to say that the company doesn’t still generate massive profits, but rather these profits have greatly diminished and worse, the general disdain for the company, it’s practices and ethics, seems to be at an all time low. I often quickly change the channel, embarrassed to think of all of the times that I’ve publically heralded them as a company to emulate!

I reassure myself by revisiting the fact that their growth and success for those 14 years was almost unparalleled, those lectures I gave were valid and useful, that there’s an element of British keenness to knock down the uber successful and then try to muse on ‘what went wrong’ to incorporate in future public appearances.

For a long time, the Tesco Board’s priority was growth achieved by securing LIFETIME customer loyalty – they sought to achieve this by, rightly, focusing on customer satisfaction but also diversifying into every aspect of our lives – ‘hooking us in’. Perhaps however they became too complacent and too greedy – focusing on achieving the desires of the customers that they already knew. They did not consider to enough extent, how a customer’s buying habits and desires might change. How they might not like Tesco being involved in every aspect of their lives! Focusing too much on their own success and not looking over their shoulder at the emergence of competitors with new business models is very dangerous. Of course, such is the peril of becoming a monolithic sensation … you become too slow, too unresponsive, too introverted and blind to lighter, more innovative newbies.

When I think about how I will teach future lectures about the importance of the Board, I will continue to use Tesco as a case study. I’ll talk about the power of persuasive leadership (things did seem to change dramatically when Leahy stepped down) and the importance of clear, concise, customer focused strategy that is cascaded through the company. I’ll also be very clear on the importance of flexibility – to keep looking around at your competitors and stretching your imagination for new ideas. I’ll also talk about the importance of business ethics and how in the 21st Century, customers are increasingly keen to spend their money at companies they respect and trust.

Cyber Security: Learning from the Movies

As a lover of lean thinking, I appreciate any development that simplifies my life. Consequently, my heart skips with delight when I pay for anything using my “contactless” debit card and love when I can pay for an iTunes download merely using my thumb print on my iPhone.

However, not everyone I know is keen on such helpful additions. I regularly am drawn into a debate with my friend who is highly suspicious of contactless technology for instance – “what if your card get’s stolen?” “what if someone steals your details just by standing next to you?”. I usually combat such statements by stating that it’s more dangerous to constantly input your pin in public, there are spending limits etc. But obviously, cyber security is a problem whether it’s people stealing your identity or copying the keycode on your car

Whilst it can be said that the exponential growth in technological capability aids cyber criminals’ activities, I cannot believe that these same advances are not being passed onto the innocent consumer, making the internet a safer place to be.

To me, the digital enhancements within the world we live in is making everything seem more and more like Tom Cruise’s 2002 film Minority Report. In that film, adverts addressed people by name as they walked past and information was accessed by air gestures and voice recognition.

After some googling, it seems that Spielberg established a “2054 thinktank” of noted cyber luminaries to help to create a plausible “future reality” as opposed to a more traditional “science fiction” setting. The thinktank worked, as so many of the futuristic features of that film are already part of our reality, indeed, in 2010 the Guardian published an article entitled “Why Minority Report was Spot On’

So what about some of the more extreme aspects of the film? Human “precogs” who are able to see into the future, predict crime and enable criminals to be prosecuted BEFORE they actually commit a crime? Well whilst I’d question whether the human race will evolve to possess psychic powers in the short term (!), it seems to me highly sensible, if deeply controversial, to develop mechanisms to analyse cyber activity to the extent where it can predict future criminal activity. Some might say that counter terrorism units already use these methods.

It also seems likely that the very fabric of who we are will be used within cyber security – Nymi is an electro cardiogram device which is able to confirm identity using our unique heartbeats – It doesn’t seem long before computers will be able to check the very DNA of who we are in order to determine that we are indeed, who we say we are.